BBC

BBC

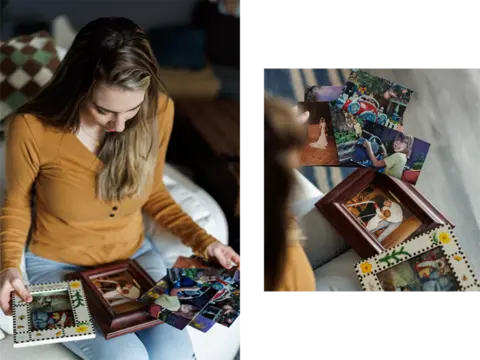

When Jordan Lux blocked her mum's phone number and deleted her from social media, she was resolute about them never speaking again. Such was the hurt and resentment that Jordan, who was 25 at the time, felt towards her mum.

The pair were estranged for almost three years, but eventually managed to tread a long and delicate path back into one another's lives.

Jordan and her mother Danni Ackerman offer a rare both-sides perspective on family breakdown and what it can take to reconcile.

"It's taken about six years of slowly learning, having fights, hanging up the phone angry, and not being able to communicate properly," says Jordan, now 33, speaking from her home in California.

She is joined on our call by Danni, 59, in Las Vegas, who is very candid about how much she "messed up and wasn't there" for her daughter. Therapy, alongside lots of "painful" conversations with her daughter, has helped them to start sifting through their "family messiness and complexity".

An ongoing feud within the Beckham family finally exploded into the open in late January, fuelling debates about adult children going "NC" - no contact - with their parents. Brooklyn Beckham posted on Instagram that he "does not want to reconcile" with his parents, whom he said have controlled and emotionally manipulated him throughout his life. His parents have not commented.

Online comments have been predictably divided: while some have called him "spoiled" and "ungrateful" towards David and Victoria Beckham, others have applauded the 26-year-old for standing up for himself and prioritising his mental health.

Danni and Jordan are both keen to stress that estrangement can sometimes be necessary.

"We are not saying everyone should be trying to get back together with their families," says Danni.

Dave Benett/Getty Images

Dave Benett/Getty Images

There is relatively little research on estrangement, but studies from Germany and the US suggest it is more common than people might think.

He has also conducted in-depth interviews with 100 people who have repaired family rifts.

He is keen to make clear that sometimes people were estranged for good reason and for whom seeking reconciliation was not the right choice.

"For example, individuals who had endured emotional abuse, chronic disrespect, or relationships so draining that continuing contact threatened their wellbeing.

"The key is making that decision thoughtfully and with self-awareness, rather than in the heat of anger, so you can live with it peacefully going forward."

Estrangement is on the rise, because younger generations have a much "broader language" for what counts as parental harm and trauma, according to psychologist Dr Joshua Coleman, who specialises in family estrangement and reconciliation, having experienced both with his own daughter. He explains that younger generations are more comfortable in asserting their needs and setting boundaries.

"Today, really every letter I see from an estranged adult child says, 'I have to do this to protect my mental health'," he says.

Parents need to take an approach to conflict with their children that is "careful and curious, interested and empathetic", he adds.

"This is really the first generation of parents who've had to do this kind of work."

This required shift in mindset has proven challenging, admits Danni.

"Jordan has had access to a lot more information in her formative years - and I'm a more stubborn Gen X.

"At first it felt like she was trying to change me, and I just wanted to be accepted - I think that's where our battles have come from."

At whatever age, cutting ties with a parent is rarely done lightly, and almost always stems from "emotional hurt and wounds that haven't been addressed", says psychotherapist Owen O'Kane, a former NHS mental health lead. "Someone within that family or that dynamic has got badly hurt."

Jordan traces her own harms back to her childhood.

She did not feel it at the time, but she was living on the fault lines of an ugly custody battle between her parents, who both went on to remarry.

This, and the turbulent years that followed, took its toll on her mental health and her ability to form secure relationships, she says.

"It felt as if she [my mum] only wanted to be a part of the good parts and we didn't discuss the bad ones."

For Danni - who says being Jordan's mum was "a joy" - it is painful to hear.

Both agree they struggled to establish a relationship with an emotional connection as adults.

The final straw for Jordan came in 2017.

"I decided to cut off contact with my mum when she told me about her divorce to my stepdad and wanted sympathy from me.

"At the time I was still mad that she didn't leave him sooner," she says, explaining how she felt her mum always put her partner above Jordan's own wellbeing.

The abrupt end to their contact felt like "torture" for Danni, who lived in "ignorance of what was truly going on".

"I would tell my friends, 'I don't know why she won't talk to me'," she recalls.

Jordan, meanwhile, fell into a fog of grinding work, drinking too much and dealing with her own relationship problems.

Estrangement is often described by therapists as a "living" or "ambiguous" loss - as they grieve a loved-one who is still alive but with whom the relationship has ended.

"For parents, there will be a fear of judgement - what have you done to bring this on?" says Dr Lucy Blake, a senior lecturer in psychology at the University of the West of England and author of No Family is Perfect: A Guide to Embracing the Messy Reality.

"It can be a particularly stigmatised experience for women, and especially women of a certain generation, where motherhood may be central to their identity."

Danni tried to keep busy and hold on to the hope that her daughter might come back around.

Almost three years passed and then, out of the blue, Jordan's number flashed up on her phone. She picked up immediately.

Jordan had left her relationship and begun to see a therapist, who had caused her to ruminate over her estrangement from her mum.

"I felt elated [...] I got to be there and be her mum again," says Danni.

It would be several years, however, until she did not feel as if she was walking on eggshells, terrified that she might put a foot wrong and have her daughter leave again.

The pair have begun talking about their relationship on YouTube and Danni has received lots of messages from people of a similar age, who she says, "are not ready to listen".

"It is hard to have your adult children tell you the things that are wrong with you as a parent," she says. "It's so painful - but I was ready, I wanted to be a better mum."

The numbers of adult children and their parents who reconcile is hard to know, but the factors behind success stories are "strikingly consistent" in Cornell's research, says Pillemer.

Those who managed to reconcile were the parents who could let go of the need for their adult child to apologise or agree on past events, and instead focus on building a future relationship.

"Critically, they also engaged in genuine self-examination about their own role in the estrangement, moving past what I call 'defensive ignorance' - that is, where people claim to have no idea why the rift occurred while simultaneously listing a history of conflict," says Pillemer.

Sending a letter or an email to your estranged child could be a good way to broach the subject of reconciliation, say some therapists.

"The language should be open and not accusatory," says O'Kane. "I miss spending time with you, I would like us to sort this out."

That letter needs to be sent with a willingness to listen "and hear that there may be other possibilities outside of the story I am telling".

In some cases, reconciliation might be partial - being able to go to the same family functions and be civil, for example. Or it may not be possible at all.

Sandra, in her 60s and from Wolverhampton has been estranged from her son for three years.

She "never really hit it off" with his girlfriend, she says, and things came to a head when she found out via Facebook that a family celebration had taken place without her, but had included the girlfriend's parents.

"It really upset me to see the photos of everyone together having fun and probably laughing at me sat indoors," she says.

The mum-of-three made some comments beneath the post which were met with fury by her son and some other family members. The pair had a late-night argument, which Sandra realised towards the end had been broadcast on speakerphone.

"I do regret what I posted and I know it was wrong - but I don't think I deserve all this," she says. "I've tried to make contact with my son more than once, but he refuses to reply."

For Danni and Jordan, there were three crucial steps to reconciling: not being defensive, realising their reconciliation might take time, and understanding there needed to be boundaries.

Jordan is now happily married and has become a parent herself. She is moving house soon and Danni will be flying in to help pack her daughter's life into boxes.

They will have fun along the way, says Jordan.

"Before now, I couldn't imagine wanting her around during such a stressful time. Now, I am so thankful that she can come."

Photography: Danni Ackermann by Ronda Churchill and Jordan Lux by Elisa Ferrari

Family photos courtesy of Jordan

3 weeks ago

39

3 weeks ago

39