BBC

BBC

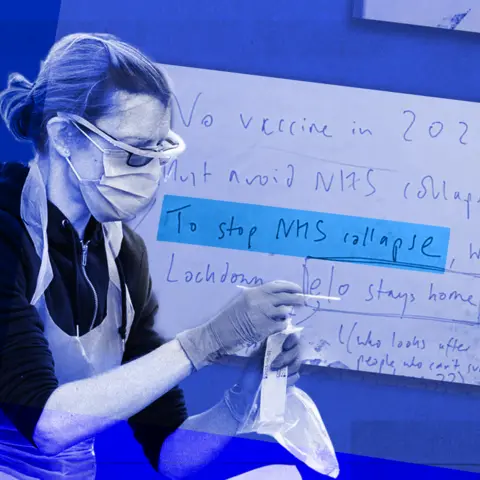

It was the most momentous event in UK history since World War Two. As a new virus took hold, millions of us were told to stay at home and billions of pounds were spent propping up the country's economy.

The Covid inquiry will publish its second set of findings later today, looking in detail at the huge political choices made at the time - including how lockdowns were introduced, the closure of businesses and schools, and bringing in previously unthinkable social restrictions.

"Did the government serve the people well, or did it fail them?" asked the lead counsel at the start of this part of the inquiry in 2023. Since then more than 7,000 documents have been made public from the time, including WhatsApp chats and emails, private diaries and confidential files.

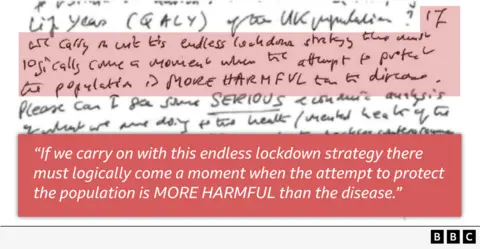

Here, BBC News has picked out some of the urgent messages and scribbled notes that shine a light on how critical decisions were taken in 2020.

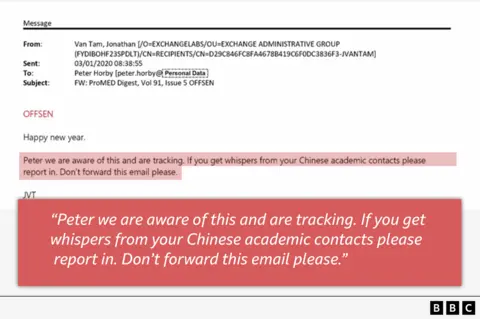

On 2 January 2020 an update appears on ProMed, a service used by health workers to warn of emerging diseases.

"World Health Organization in touch with Beijing after mystery viral pneumonia outbreak," it says.

"Twenty-seven people - most of them stallholders at the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market - treated in hospital."

The next day England's deputy chief medical officer, Jonathan Van Tam, sends the bulletin on to Peter Horby, a professor at Oxford University and chair of Nervtag, a group that advises the government on new viral threats.

By the end of January, it's clear the health authorities in Wuhan have a major problem on their hands.

The deputy ambassador to China, Christina Scott, sends a cable back to London marked DIPTEL BEJING (Sensitive) comparing the situation to the outbreak of another virus - SARS - in 2003.

"Hubei province on lockdown; multiple cities have transport restrictions. Memory of SARS cover-up ensures residual distrust of government response," it says.

"They will do everything they can to quickly control this outbreak. But the challenge of doing so is substantial."

The virus spreads to Hong Kong and South Korea and then to Iran and northern Italy.

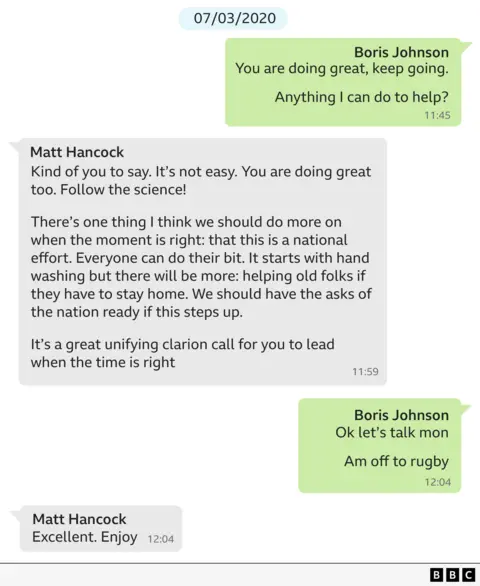

At lunchtime on Saturday 7 March the UK's then prime minister, Boris Johnson, is chatting on WhatsApp to his health secretary Matt Hancock ahead of the England vs Wales game at Twickenham.

Days later, the Cheltenham horse racing festival goes ahead and Atletico Madrid fans are allowed to fly from Spain to Liverpool to watch their team play in the Champions League.

The government's strategy, backed by its scientific advisers, is to try to contain early outbreaks by isolating those with the virus and tracing any contacts.

The plan is then to move to a "delay phase" as full community transmission is established – using policies like home isolation advice for those with symptoms to "flatten the curve" of the pandemic so that hospitals do not become overwhelmed.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Boris Johnson shook hands with England captain Owen Farrell at the rugby match at Twickenham on 7 March

But the virus is spreading much faster than expected and it‘s quickly becoming clear to many scientists that far stronger action will be needed.

On Friday 13 March, two senior No 10 officials are sitting in a key meeting of scientific advisers in Whitehall.

"WE ARE NOT READY," one writes in capital letters in his notepad. The other leans over and crosses out "NOT READY", replacing it with an expletive.

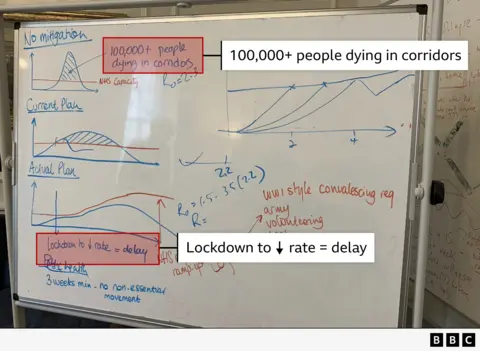

That weekend, the prime minister's chief adviser, Dominic Cummings, is locked in a series of meetings with the PM and a handful of select staff as a new strategy takes shape.

Covid Inquiry

Covid Inquiry

Dominic Cummings in the prime minister's office - he said others in the room included Boris Johnson, special adviser Chloe Watson, and director of communications Lee Cain

Grainy smartphone images show whiteboards in No 10 full of hand-drawn charts and scrawled bullet points.

One graph suggests that, if the virus was allowed to run its course without any restrictions in place, then more than 100,000 people would die "in [hospital] corridors" in the coming wave.

On Sunday 15 March, Cummings sends a WhatsApp to Johnson:

"FYI – [Patrick] Vallance [the chief scientific adviser] is on board with what will NEVER be discussed as Plan B."

"[In a] nutshell: we move through the gears to [do] whatever we need to stop NHS collapse and buy time to increase capacity."

Over the following week, Covid rules across the UK are tightened.

People are advised, but not legally required, to avoid all non-essential contact and work from home where possible. Then schools are closed, followed by pubs, restaurants, gyms and cinemas.

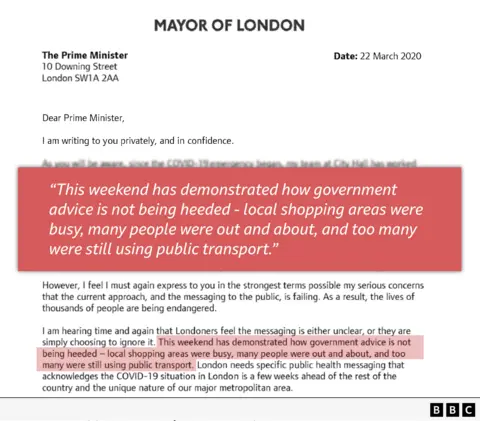

But still there are concerns that even those measures are not strong enough. On Sunday 22 March, London's mayor, Sadiq Khan, writes a private letter to Johnson.

The next evening, in a televised address watched by 27 million people, the prime minister tells the public they must stay at home as he announces the first national lockdown.

It will now be up to the inquiry to decide if making that call earlier could have saved lives and ultimately reduced the total time that people had to stay locked indoors.

Controlling Covid and protecting the economy

Over the next month some hospitals do come under severe pressure with intensive care units spilling into corridors and side rooms. Pre-planned or elective care is put on hold but at no point does the NHS have to turn away emergency patients.

Covid infections, hospitalisations and deaths start to fall.

But the cost of lockdown restrictions is huge: education is disrupted, loneliness and mental health problems get worse, and jobs and businesses are impacted.

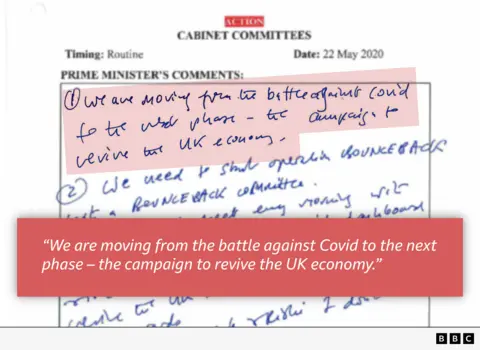

On 22 May, Johnson sends a handwritten note to his officials asking for a plan to "start operation BOUNCEBACK".

That month some restrictions begin to be lifted – soon groups of six are able to meet outdoors and schools start a phased re-opening.

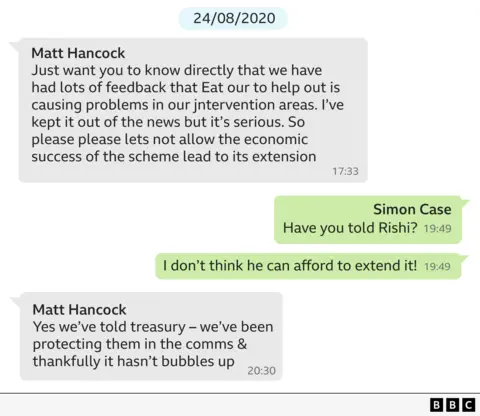

In the summer, then-chancellor Rishi Sunak tries to boost the economy with his Eat Out to Help Out scheme - 50% off food and drinks for three days a week in August.

The idea is well received by the hospitality industry but there are concerns about the health impact.

On WhatsApp (with spelling mistakes), Hancock warns Simon Case, then the most senior civil servant in Downing Street, that it's causing problems in intervention areas - that’s those local authorities with the highest infection rates.

In his evidence to the inquiry, Sunak plays down a link between his scheme and the spread of the virus saying a second wave "happened in every other country in Europe".

But that tension – between controlling Covid and protecting the economy – becomes even more intense through the autumn.

Many scientists advising the government want to see tighter rules. They campaign for a short "circuit breaker" lockdown to try to drive down infections.

At times the documents suggest the prime minister supports tougher restrictions, at others he appears determined to avoid another strict national lockdown at all costs.

PA Media

PA Media

Rishi Sunak, wearing a mask in the summer of 2020, was a key proponent of the Eat Out to Help Out scheme

On WhatsApp Johnson's closest aides complain about his decision-making – using an emoji of a broken trolly as he appears to swerve from one policy position to another.

"This government doesn't have the credibility needed to be imposing stuff within only days of deciding not to," writes Case, who is now the new cabinet secretary, to Cummings and Lee Cain, No 10 director of communications, on 14 October.

"We look like a terrible, tragic joke. If we were going hard, that decision was needed weeks ago. I cannot cope with this."

In his testimony to the inquiry, Case later says he regrets expressing his "at-the-moment frustrations" with Johnson, whom he "barely knew" at the time.

In his evidence, Johnson defends his own leadership style, saying his views changed with the scientific evidence, and he often adopted certain positions because he wanted to hear the counter arguments.

Second national lockdown

As the nights draw in that autumn, it becomes clear that existing restrictions in England - including a 10pm curfew and the so-called tiered system of local controls - are not going to be enough to control the virus.

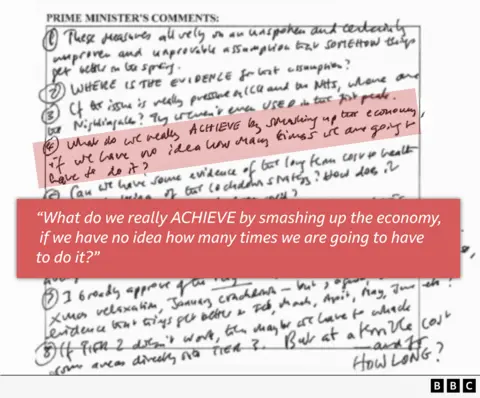

By the end of October, the prime minister's frustration is obvious in the long note he scrawls at the end of a Covid briefing document marked OFFICIAL/SENSITIVE.

In tightly-spaced handwriting, Johnson pens 22 detailed points over two A4 pages of the document.

He approves of strengthening some local restrictions but bemoans the "terrible cost" and wonders "for HOW LONG?"

"Is NHS T&T [test and trace] actually achieving ANYTHING?" he asks at one point.

A week later, on 5 November 2020, England does enter its second national lockdown, this time lasting four weeks, although most schools remain open.

By this point many decisions are being taken independently by the four nations of the UK. Both Wales and Northern Ireland put in place versions of a circuit breaker lockdown, while in Scotland stricter rules are imposed in the central belt.

The plan is still to allow families and friends to meet up at Christmas.

But by mid-December a new, more infectious variant of the virus is spreading and millions living in the south-east of England are told at short notice that Christmas mixing will be cancelled.

In January 2021, a third and final full national lockdown follows across the UK, as the winter wave peaks and the NHS starts rolling out millions of doses of the first Covid vaccines.

Lessons learnt

Five years on from those dramatic 12 months, the inquiry's findings are long-awaited, particularly by the 235,000 families who lost loved ones in the pandemic.

The messages and documents highlighted here are just a snapshot - the report due later will run to around 800 pages.

It will examine some of the key questions in much more detail: the timing of lockdowns, the impact of restrictions on the most vulnerable, and public confidence in the rules amid reports of partying in Downing Street and other alleged rule breaches.

Groups representing thousands of bereaved families want individuals working in government at the time to be held to account for any pandemic failings.

But - above all - they want the state to learn lessons from any mistakes and be better prepared if and when the next unknown virus arrives on our shores.

Some documents in this article have been recreated. All contain the original texts including spelling mistakes and typographical errors.

Additional reporting: Pilar Tomas and Ely Justiniani, BBC Visual Journalism Unit.

Top image credit: Getty/BBC

2 months ago

48

2 months ago

48