Chris Baraniuk

Technology Reporter

Getty Images

Getty Images

Subsea cables are critical to the operation of the internet

The diver had found the fibre optic cable lying on the seabed of the North Sea. He swam closer, until it was near enough to touch.

He reached out his hand. But someone could tell he was lurking there. Someone was watching.

"He stops and just touches the cable lightly, you clearly see the signal," says Daniel Gerwig, global sales manager at AP Sensing, a German technology company. "The acoustic energy which travels through the fibre is basically disturbing our signal. We can measure this disturbance."

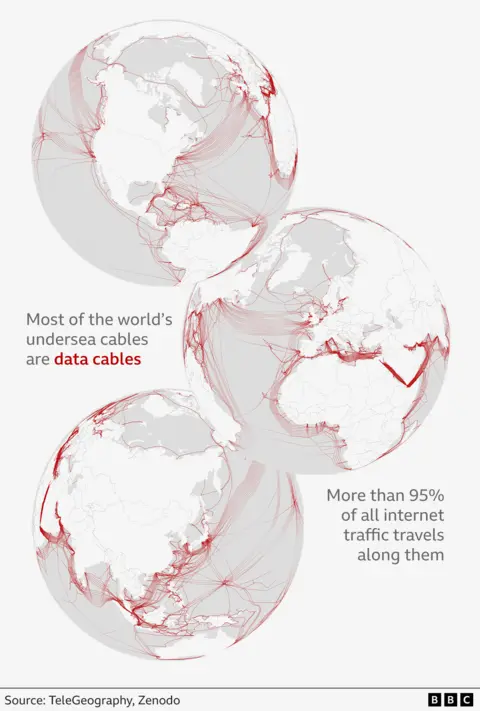

Multiple reports of damaged telecommunications cables in the Baltic Sea have raised alarm in recent months.

So important are these cables, which carry huge volumes of internet data between countries, that Nato has launched a mission called "Baltic Sentry", to patrol the Baltic Sea with aircraft, warships and drones.

The EU is also stepping up measures to monitor and protect cables.

Despite those efforts the authorities cannot be everywhere at once.

So, some companies are trying to monitor what's going on in the vicinity of any cable – by using fibre optic signals to listen out for surreptitious underwater drones, or hostile vessels dragging their anchors along the seabed.

It was during tests of AP Sensing's system last year – not a real attempt at sabotage – that the diver patted his hand on the subsea cable watched over by the firm.

The company also deployed ships, drones and divers with sea scooters to find out how accurately its software could pick out and identify the presence of these vehicles.

And, the team tested whether their cable could "hear" a vessel plunging its anchor into the water.

When pulses of light travel along a fibre optic strand, tiny reflections sometimes bounce back along that line. These reflections are affected by factors including temperature, vibrations or physical disturbance to the cable itself.

Noticing a temperature change along part of a buried cable could reveal that part has become unburied, for example.

AP Sensing shows me a video of a man walking across a lawn before lifting up a rifle and firing it during a test. A fibre optic cable buried in the ground a few metres away picked up the whole sequence.

"You see every single footstep," says Clemens Pohl, chief executive, as he points to a chart revealing disturbances in the fibre optic signal. The footsteps appear as brief blips or lines and the gunshot as a larger splodge.

With this technology, it is even possible to work out the approximate size of a vessel passing above a subsea cable, as well as its location and, in some circumstances, its direction of travel. That could be correlated with satellite imagery, or even automatic identification system (AIS) records, which most ships broadcast at all times.

It is possible to add monitoring capabilities to existing fibre optic cables if one unused, "dark" fibre is available, or a lit fibre with enough free channels, the firm adds.

There are limitations, however. David Webb at Aston University says that fibre optic sensing technology cannot pick up disturbances from very far away, and you need to install signal listening devices, or interrogators, every 100km (62 miles) or so along a cable.

AP Sensing says that it can pick up vibrations hundreds of metres away but "usually not several kilometres away". The company confirms that its technology is currently deployed on some cable installations in the North Sea, though declines to comment further.

"People really need an early warning in order to determine what to do," says Paul Heiden, chief executive of Optics11, a Dutch firm that also makes fibre optic acoustic sensing systems.

Mr Heiden argues that cables installed solely for the purpose of monitoring marine activity could be especially useful – one might place such listening cables, say, 100km from a vital port, or in the vicinity of a key gas pipeline or telecommunications cable, rather than within those assets themselves.

That could give operators an overview of vessel traffic in the area, and potentially advance notice of a ship heading towards a critical asset.

Hexatronic

Hexatronic

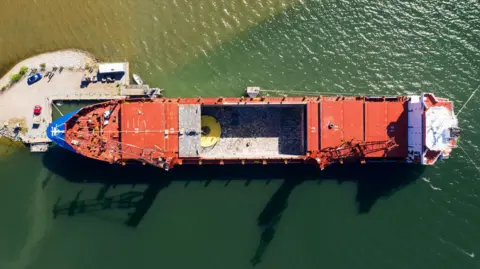

Cable laying vessels connect up continents

Optics11's fibre optic listening technology can be deployed on military submarines, Mr Heiden adds, and he says the firm is soon to begin testing a monitoring cable installed somewhere on the floor of the Baltic Sea.

Demand for fibre optic sensing technology is growing, says Douglas Clague at Viavi Solutions, a network testing and measurement company: "We do see the number of requests increasing."

Some of the cables damaged in recent incidents were made by Swedish cable company Hexatronic, says Christian Priess, head of Central Europe, Middle East, Africa and submarine cable business at the firm.

Acoustic sensing is an emerging technology that Mr Priess suggests will become more common in the future. But there's relatively little one can do to protect a cable from sabotage, in terms of physical strengthening.

Today's fibre optic cables already have metal casings folded and welded shut around the fibres, he says. There is also "armoury wire", thick metal cords, running along the outer parts of the cable and in some cases there are two layers of these cords. "On the UK side of the Channel where you have a lot of rocks and a lot of fishing, you want to have it double-armoured," says Mr Priess.

Optics11

Optics11

Although heavily protected, cables are still vulnerable

But should a vessel deliberately drag its heavy anchor across even a double-armoured cable, it will almost certainly still damage it, Mr Priess says – such is the force of the collision or pulling action.

While it is possible to bury cables in the seabed for additional protection, this might become prohibitively expensive over long distances and at depths below a few dozen metres.

"Cables break all the time," says Lane Burdette, research analyst at TeleGeography, a telecoms market research firm. "The number of cable faults per year has really held steady over the last several years," she adds, explaining that the 1-200 faults that typically occur annually has not risen despite ever more subsea cables being installed during that period.

Ms Burdette also notes that, even when a cable is severed, telecommunications networks typically have significant redundancy built into them, meaning that end users often don't notice much disruption to their service.

Still, the visible military response to cable breakages in the Baltic Sea is welcome, says Thorsten Benner, co-founder and director of the Global Public Policy Institute, a think tank: "It's good that Nato and the European Union have woken up."

And while cable sensing technology might be useful, its efficacy in terms of preventing damage rests on how quickly coastguard or military patrols could receive alerts about potential sabotage and react. "The question is how quickly you could establish contact with a vessel," Says Benner.

More Technology of Business

1 month ago

67

1 month ago

67