Laura GozziBBC News, Kyiv

BBC

BBC

Daria worries about forming a connection with a soldier, only for them to have to leave

Sitting in a wine bar in Kyiv on a Saturday night, Daria, 34, opens a dating app, scrolls, then puts her phone away.

After spending more than a decade in committed relationships she's been single for a long time. "I haven't had a proper date since before the war," she says.

Four years of war have forced Ukrainians to rethink nearly every aspect of daily life. Increasingly that includes decisions about relationships and parenthood – and these choices are, in turn, shaping the future of a country in which both marriage and birth rates are falling.

Millions of Ukrainian women who left at the start of the 2022 full-scale invasion have now built lives and relationships abroad. Hundreds of thousands of men are absent too, either deployed in the army or living outside the country.

For those women who stayed, the prospect of meeting somebody to start a family feels increasingly remote.

Khrystyna, 28, says it's noticeable that there are fewer men around. She lives in the western city of Lviv and has been trying to meet a partner through dating apps without much luck.

"Many, I would say most [men] are afraid to go out now, in this situation," she says, raising her eyebrows. She is referring to the men of fighting age who spend most of their time indoors to avoid the conscription squads roaming the streets of Ukraine's cities.

As for soldiers, "many are traumatised now because most of them – if they have returned – were in places where they experienced a lot", she says.

Daria feels much the same. "I only see three options here," she says, listing the types of men she believes are available to women like her.

First are those trying to avoid conscription. Someone who can't leave the house is probably "not a person you want to build a relationship with", Daria says.

Then there are soldiers, forced into long-distance relationships with sporadic visits from the front line. With them, Daria warns, "you build a connection, then he leaves".

The remaining option, she adds, are men under the conscription age of 25. But those aged 22 and under can still leave the country freely, and Daria says they could take off at any moment.

None of these appeal to her.

Supplied

Supplied

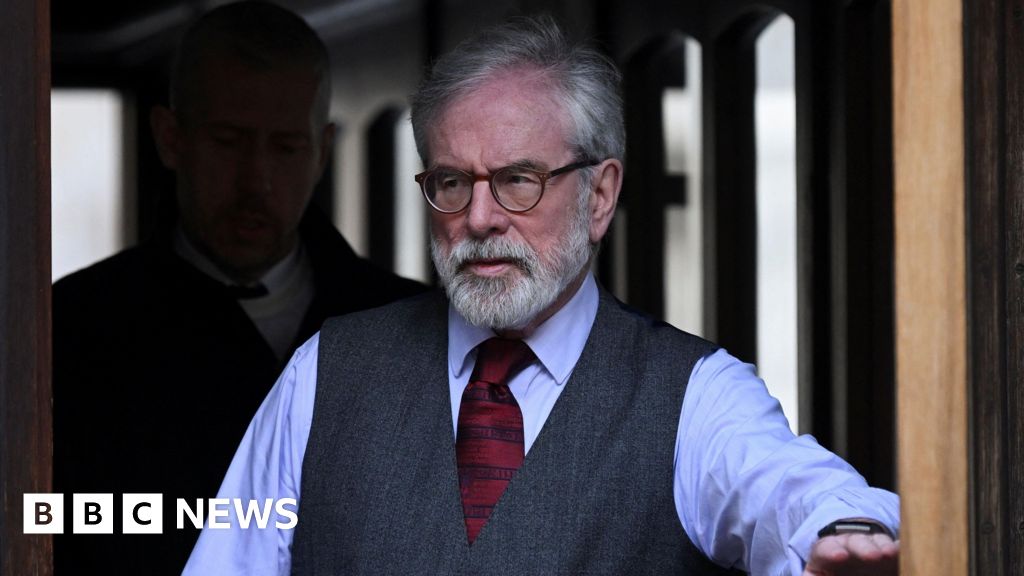

Drone operator Denys says the war makes it difficult to promise long-term plans to a partner

Closer to the front line, many men on active duty are also shelving the idea of starting a a relationship. Uncertainty, they say, makes long-term commitments feel irresponsible.

Ruslan, a soldier serving in the Kharkiv region, knows the promises he can make are limited. Beyond visits once or twice a year, flower deliveries and the odd phone call, he asks, "what can I actually offer a girl right now?"

"Promising a wife or a fiancée any long-term plans is difficult," says Denys, a 31-year-old drone operator, in a voice message sent from his position in the east of the country. "Every day there is a risk of being killed or injured, and then all plans will, so to speak, go nowhere."

The consequences of this disruption threaten to ripple far into Ukraine's future.

In many ways, they already have. Since the start of the invasion, the number of marriages has decreased sharply from 223,000 in 2022 to 150,000 in 2024.

Ukraine has also seen deaths increase, enormous emigration – more than six million people have left the country since 2022, according to an UN estimate – and a stark decline in birth rates.

These all lead to a dramatic drop in population, which in turn shrinks the workforce and slows economic growth.

Oleksandr Hladun, a demographer at Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences, describes these trends as the "social catastrophe of war".

And this follows Ukraine's population declining between 1992 and 2022, from 52 million to 41 million, due to a high mortality rate, migration and a decline in birth rates.

Birth rates have dropped even lower during the conflict. In 2022, numbers were partly sustained by pregnancies from 2021, Hladun told Ukrainian media earlier this year. In 2023, some couples had children in the hope the war would end.

But in 2024, when it became clear peace was not imminent, the birth rate fell sharply. It now stands at 0.9 children per woman, a record low, and far below the 2.1 children needed to maintain the population (for comparison, the total fertility rate in the EU is 1.38).

While a decline in births is to be expected during war, Hladun says, it is generally followed by a peacetime compensatory increase thanks to those who postponed having children. But this effect is limited, usually lasting up to five years – too short a time to have a significant effect on Ukraine's bleak long-term prospects.

"The longer a war lasts, the smaller this compensatory effect becomes," Hladun adds, because couples who put off having children during the conflict no longer get the chance to do so. "And for us it has already been four years, which is quite a long period."

According to the National Academy of Sciences, the effects of the war will last well beyond the end of hostilities – which, in any case, is not in sight. The result, it says, could be a population of 25.2 million people by 2051, less than half what it was in 1992.

Even committed couples suffer from the uncertainty of war.

Olena, 33, has come to a fertility clinic on the outskirts of Lviv for a check-up. She is a policewoman and military instructor who is currently freezing her eggs, as health issues have made it difficult for her and her husband to conceive.

At some point, Olena says, they will try IVF – though only while "taking into account my work and the situation in the country".

Dr Liubov Mykhailyshyn, right, is worried that the war is affecting the fertility of young Ukrainian couples

Olena remembers life before the war as beautiful and "full of hope". But her dreams of starting a family were put on hold by the start of the invasion in 2022.

"During the first year of the war, it felt as if everything had stopped," she says. "Everything we were striving for – building a home, planning children – nothing mattered anymore."

Those fears haven't disappeared, even in Lviv, which like other parts of western Ukraine has, comparatively, been spared the worst of Russia's attacks. But for Olena, the question of having children now carries a sense of duty. "I am doing this both for myself, and for my family, and for Ukraine," she says. Soldiers on the front line, she believes, also die for the sake of unborn Ukrainian children.

On the other side of the desk, Olena's gynaecologist and clinic director Dr Liubov Mykhailyshyn listens.

She is proud to help "strong, nice women" like Olena, she says. But her big concern is the way the war is affecting the fertility of young Ukrainians.

She worries about years of chronic stress and sleepless nights – as well as the additional physical and psychological trauma for those on the front line. All of these, she says, can cause fertility problems, which could have an impact on birth rates in the years to come.

"We are waiting for it," Mykhailyshyn says of the demographic crisis ahead. Olena nods.

Recently, the Ukrainian government developed strategies aimed at tackling the problem, including affordable childcare and housing. These policies, however, rely on local authorities rather than centralised funding – meaning projects often don't take off, according to Hladun.

And as long as would-be mothers and children remain exposed to the dangers of war, state-level efforts might not find much success, he concedes.

Ukraine now has 17 million fewer people than when it gained independence after the fall of the Soviet Union. Only a return of a substantial proportion of the 6.5 million Ukrainians who live abroad could boost figures quickly.

Yet even when the fighting stops, it is unclear how many will come back.

People will be more willing to return if Ukraine is able to regain most of the territory seized by Russia since 2014, Hladun suggests. But anything short of that could leave Ukrainians feeling vulnerable as it would be considered a temporary ceasefire rather than a complete end of hostilities.

Despite insistence from Moscow that it does not wish to take over the whole of Ukraine, many Ukrainians are convinced that Russia poses an existential risk to their country – and one that will outlast Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In this context, Ukraine's population decline should be seen as a security threat, says Hladun. "Russia is simply demographically much larger," he argues. "And in this sense, it has more resources for war."

The longer the war continues, the more the uncertainty will dent the country's prospects for long-term recovery.

"Planning a future feels fragile, almost naive," Daria says. "This uncertainty is painful, but it becomes a part of everyday life.

"I've come to accept that I might stay alone not because I want to, but because war reshapes what feels possible," she adds.

"Learning to live with that is, in itself, a form of survival."

Additional reporting by Liubov Sholudko.

1 month ago

64

1 month ago

64