Laura Kuenssberg

Presenter, Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg•@bbclaurak

BBC

BBC

It's a strange feeling, sitting down with someone who once had huge power and now does not.

The change from before to after can be hard to describe. It's often in their demeanour, nervous when once they bossed the room. Alone or with one supporter when once they had an entourage carrying their bags or demanding to see the camera shot. Sometimes they're angry, if they believe they've been wronged out of their job; sometimes bristling with ambition, their exit itself a bid for influence.

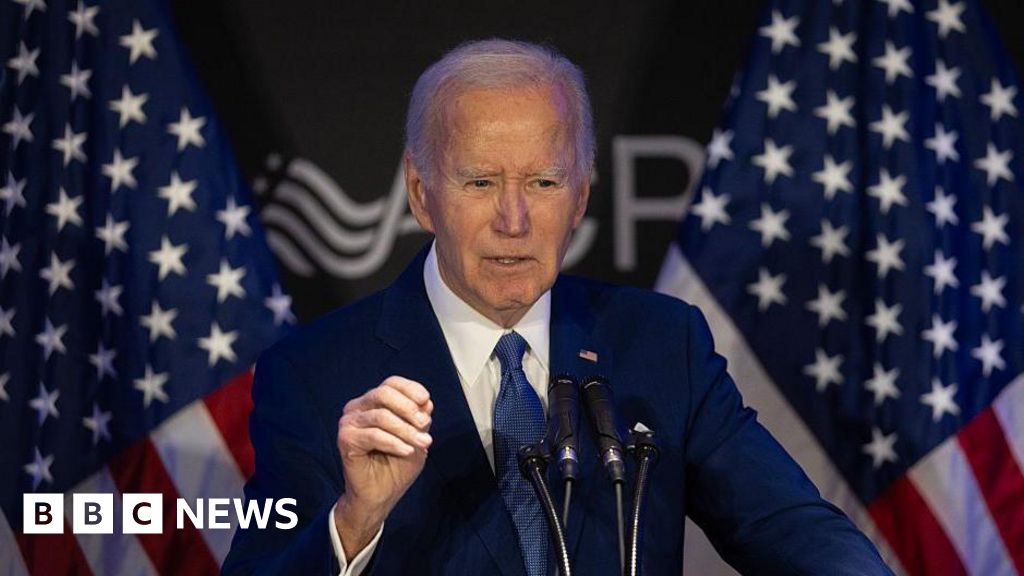

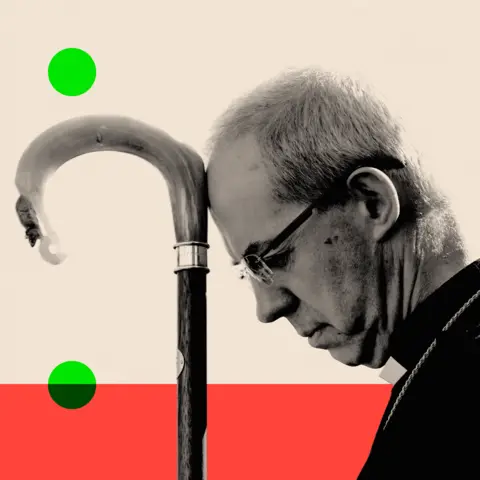

Justin Welby walked into the room for our interview without the Archbishop's sumptuous garb. No crucifix, not even a simple dog collar. Just "Bishop Justin" now, with no pulpit to preach from, and perhaps not much to lose.

For more than 10 years he was the leader of the Church of England, the moral guide for a community of more than 80 million worshippers worldwide. His job was one of the most influential and important jobs in our country, stitched into the fabric of our national life, into the Royal Family, Parliament, and small-p politics.

For many of the victims of serial abuser John Smyth, and likely many of you reading this, Welby's confessed failures are not just mystifying but deeply alarming. He wasn't "curious" enough to pursue allegations of child abuse in the Church of England. He says now that when he took the job in 2013 he was too "overwhelmed" by the scale of the wider problem to check what had happened with Smyth, a man he had known for years, even though he believed the allegations were probably true.

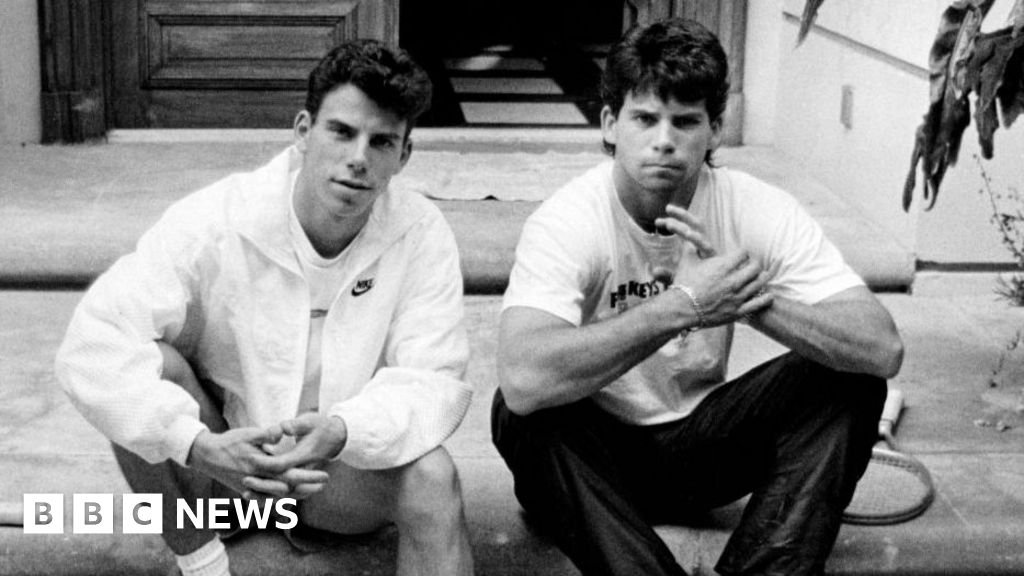

An independent review found that Smyth's violent abuse of more than 100 children and young men was covered up within the Church for decades. Smyth died aged 77 before he could be brought to justice.

.

.

Smyth was a barrister and senior member of a Christian charity

Listening carefully to Welby now, frankly, the admission that he got it so wrong is still baffling. This wasn't decades ago, when any discussion of abuse was totally taboo. There had already been high-profile prosecutions of clergy. His attitude has been seen not just as impossible to understand, but as completely tone deaf by some of those Smyth abused so appallingly, fuelling suspicions that he simply didn't want to know.

And while it's in line with his faith, the former Archbishop's statement that he would forgive the serial abuser if he was alive may cause further upset.

One of Smyth's victims, known as Graham, who made the original 2013 complaint about Smyth, told the BBC that he would not forgive Welby until victims are told the full truth about what went wrong. "Not if he continues to blank us and refuses to tell us the truth. We're the victims, we deserve to know what happened and we don't yet," Graham says.

"If in 2017 [Welby] had contacted us, said 'I will come and apologise to you personally. I am sorry. I messed up.' I would have forgiven him immediately but he never has in those terms."

Watch: Justin Welby says if Smyth were alive, he would forgive him

Welby talks freely now about what he got wrong and his sense of shame, and enthusiastically about the changes to safeguarding in the Church since 2013. But he seemed far less comfortable trying to explain why he had not, in his own words, "cared sufficiently" about reports of harm being done to young men in the Church's care – and he seemed defensive when asked if he really, truly, hadn't known anything about Smyth earlier than 2013, which the official review concluded was unlikely.

In our conversation, which you can watch or listen to in full here, there was also an overwhelming sense that Welby has unfinished business. When it comes to Smyth, Welby admitted there are still around a dozen people involved in the Church who knew about the abuse but are yet to face the consequences, while pointing out that he himself is not facing any disciplinary action.

And when it comes to the Church's sometimes woeful handling of abuse cases more broadly, there still isn't a truly independent system of safeguarding, which Welby regrets, even though he was keen to highlight the increase in the number of people working in that area.

What about other issues in the Church that he presided over for more than a decade? The equal treatment of gay couples who still are not able to have their partnership celebrated in the same way as straight partners? What about women priests, who can still be rejected by individual parishes? In the 2020s, the Church of England is not an institution that treats all of its worshippers or all of its preachers the same.

Welby's explanation? Politics. "I would've loved to be able to wave a magic wand and get it all right, or as I saw it right," he said, but he wouldn't have been able to get the votes required for the Church's governing body, the General Synod, to approve more sweeping changes.

His backers would say he was able to push forward some modernisation. His critics might say, too far, or not far enough. Some say the task of modernising the Church, with millions of members in countries around the world, in many places more conservative than the UK, is nearly impossible.

Reuters

Reuters

Could the Church split? That would be a "tragedy", he says. Isn't there a cost to the compromise to preserve the organisation? Unity takes priority, he says. "We disagree amongst each other but that doesn't stop us being family, and the role of the Archbishop and other bishops is to allow people to remain in the family without totally dismissing standards that are essential."

Welby was careful not to say he'd been treated unfairly in the frenzy that followed the revelations about the scale of his and the Church's mistakes. The reality is that the nature of his errors were not just minor imperfections, but a shocking lack of action.

Yet his words on how hard it is to be a public figure in our era might find some quiet nods of agreement in Westminster. Social media, he says, has sped up a rush to judgement, leaders put under an unforgiving glare. "If you want perfect leaders, you won't have any leaders," he says.

Does he hope for a place in the House of Lords, like many other Archbishops before him? Perhaps. Would it be granted? Given what happened, that would be a vexed question. But Welby's version of his part in the Smyth scandal, and his reflections on his time in Lambeth Palace, are now laid out for the record.

He wants now, he says, to fade into obscurity, his power and influence gone. He may perhaps preach again, but would have to ask permission from the Church.

Some of Smyth's victims may blame Welby for his attitude forever. Historians and Church experts will debate and argue about his legacy – not just his handling of abuse, but his stewardship of the Church.

Welby is not the first, nor the last, public figure whose career was brought to a painful end. But having made history for the wrong reasons, anonymity and obscurity is perhaps not his to choose.

The full interview is on iPlayer and BBC Sounds, and will show on BBC 2 on Sunday at 23:35.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Sign up for the Off Air with Laura K newsletter to get Laura Kuenssberg's expert insight and insider stories every week, emailed directly to you.

1 month ago

54

1 month ago

54