Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Noah Lyles will race in the men's 200m final in Tokyo on Friday

ByHarry Poole

BBC Sport journalist in Tokyo

When the biggest prizes are decided by fractions of a second, every detail counts.

And when you've done all you can to prepare, the ability to unsettle your rivals can provide those final, marginal advantages.

Noah Lyles, among the sport's most outspoken athletes and who will seek to retain his world 200m title on Friday, is not one to miss such an opportunity.

During last weekend's 100m competition, Lyles said he "knew" that Jamaica's Oblique Seville would make a slow start in his heat after seeing the 24-year-old "panicking" before heading out to the track.

Whatever his motive, it did not have the desired effect.

Seville produced a personal best in the final to become the first man from his nation to win a global 100m title since Usain Bolt, with the dethroned Lyles taking bronze.

On Thursday night, Lyles moved to dishearten his rivals when, having already established a sizeable advantage, he did not relent and set the fastest time this year.

"After the first 50m I thought I heard [Great Britain's] Zharnel [Hughes] running alongside me and I said to myself, 'You ain't catching me'.

"The message today was that they can't beat me. Don't miss the final, it's going to be magical."

Hughes previously admitted that disparaging comments by Lyles had "raised all the red in me" prior to last summer's Olympics, where the American would win the 100m title.

So do mind games really work in athletics? What tricks are used? And how do they play out around the sport's major finals?

'It can backfire'

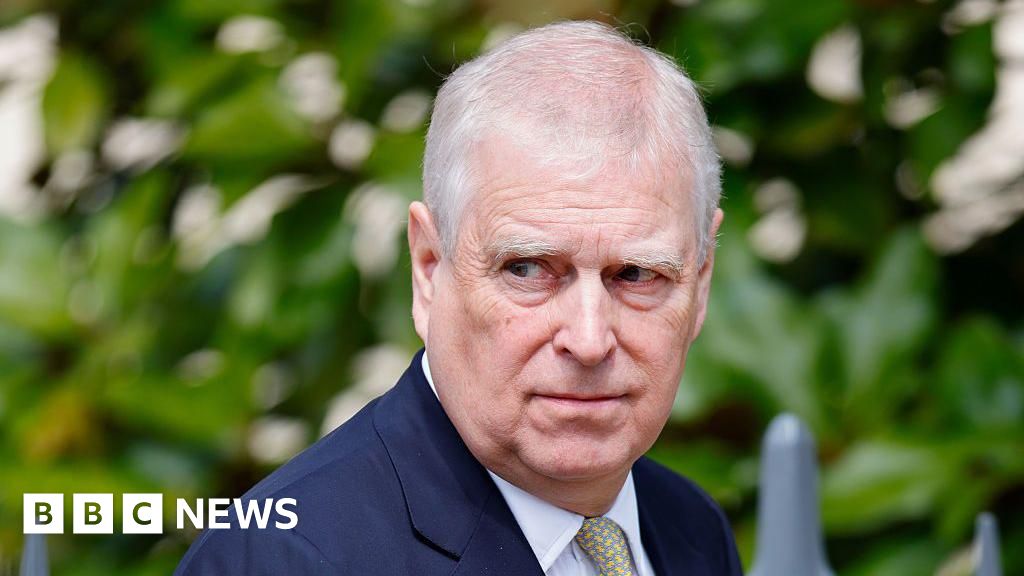

Former world 200m champion Ato Boldon is no stranger to the art of mind games - and in particular attempting to block them out.

The Trinidadian recalls one attempt to unsettle him - and indeed the rest of his competitors - by American John Capel at the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

"John Capel hadn't run in the 100m, while I was on one hamstring after getting the silver and thought I was going to have to pull out," Boldon, who added 200m bronze to his 100m silver at those Games, tells BBC 5 Live Sport.

"In the call room, Capel was shouting and psyching himself up, while trying to intimidate us.

"But he gets to the start line and, because he's so hyped up, he flinches, rocks back, the gun sounds - and I think he got dead last.

"So it can backfire."

Boldon believes Lyles may have realised his error after making his comments about Seville: "I think he wanted to say it but then he realised he may have given him fuel for the final.

"I would say 80% of performance [at major championships] is mental because everybody is strong. It's a matter of being ready for the fight. If you're not, you're done."

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Ato Boldon and his Trinidad and Tobago team members wore unique sunglasses during the men's 4x100m relay at Sydney 2000

Facing the likes of intense three-time global 100m medallist Dennis Mitchell in major finals, Boldon chose to adopt a different approach.

"My thing was that you weren't going to be able to read me," Boldon says.

"Dennis Mitchell would be hopping up and down and screaming. I used to look at that and think who are you trying to convince - me or yourself?

"It didn't work on me."

With so many dynamics at play, the call room in particular can be a daunting place for many athletes - one which has the potential to make or break a performance.

British Paralympic bronze medallist Stef Reid found call rooms to be "one of the weirdest experiences" around competition.

"It took me a couple of years to figure out who I wanted to be in that situation. Yes, I am smiley and friendly, but I also wanted to kick some serious ass," says Reid.

"It's easy to spot who is nervous and ready to crack. They're fidgety. They're checking their bag and equipment constantly, doing panic stretches and warm up drills every five seconds.

"So I did the opposite. I sat in my chair like I was lounging on the beach, full of confidence and totally unfazed.

"Mind games don't have to be loud. Sometimes quiet confidence, even if it's fake, is more off-putting."

'A real sign of weakness if anyone reacts'

There can be valuable information to be gained from paying attention to your rivals in those telling, close-quarter moments before battle, too.

Knowing how to read your competition, filtering the clearly confident from those potential poker players, is something many of the greats ensured they mastered.

"Daley Thompson was by far the best at this stuff," former world 1500m champion Steve Cram said of GB's three-time global decathlon champion.

"He saw it as a real sign of weakness if anyone reacted."

Former world marathon champion Paula Radcliffe says: "Mind games can be played everywhere. The call room is always a very interesting place to be - and here in Tokyo you also have the twist of the bus journey to the stadium to extend that."

That 20-minute bus journey from warm-up track to stadium is an additional factor extending the call room eeriness in Tokyo.

For Great Britain's 1500m silver medallist Jake Wightman, enduring a silent mini bus journey to the stadium for Wednesday's final with all his rivals was not ideal preparation.

"It is deadly silent. I don't really like silence," Wightman said.

"Through the rounds, I was trying to make conversation, and you realise not too many people want to hear you chatting.

"Before the final there's a lot of nerves. So there wasn't much conversation."

Wightman's British team-mate Josh Kerr and Norwegian Jakob Ingebrigtsen have made no secret of their attempts to unsettle each other in recent years, and Kerr often wears sunglasses so that his rivals cannot read his facial expressions.

"All of us do it in one way or another," says Cram.

"But often the so-called mind games are played outwardly by people who feel a need to address their own doubts or insecurities.

"I think a lot of it in today's world, though, is not really mind games. It's athletes just trying to get attention and exposure."

2 months ago

67

2 months ago

67