Stephen Menonand Laurence Cawley,BBC London Investigations

Getty Images

Getty Images

The key to a good Christmas cracker joke is not whether it is funny but whether it can illicit groans around a dinner table, experts say

"How much did Santa's sleigh cost? Nothing, it was on the house."

The joke is met by groans that echo through a warehouse in Lambeth, London.

We're at a joke-testing session with Talking Tables, a London company that makes supplies for gatherings. Its repertoire includes Christmas crackers.

The firm's founder and chief executive, Clare Harris grins, almost apologetically at the gag. But the joke has made the cut and will feature in future crackers.

"You measure the joke by the number of groans and the loudness of the groans around the table," Ms Harris says.

The key to a good Christmas cracker joke is not the same as a good gag per se. It is all about the context - in this case, the shared laughter of the Christmas dinner table with grandparents, children and potentially the neighbours or friends who've joined this year.

"You want the joke to be something that brings the eight-year-old together with the 80-year-old," Ms Harris says.

The BBC joined a joke-testing session in a London warehouse

Joke selection takes place on the upper level of the warehouse, where a handful of staff from across the company gather to pitch and assess the latest jokes they have come up with.

The jokes being worked through today will be the last few to make it into crackers for 2026.

The firm works at least a year in advance of the next batch of crackers.

"What do monkeys sing at Christmas?" asks Ms Harris. "Jungle bells, jungle bells."

On this occasion, there are more emphatic "noes" than groans, and Ms Harris accepts defeat this time around. It won't be found in a cracker next year.

Chloe Lloyd, who works in the sales team, pitches one of her jokes at a Christmas cracker-testing session in London

"We have a database," she says. "But each year we make sure we bring our favourites from when we've used them at home."

Cracker joke material comes from a variety of sources including the internet, word of mouth and the company's own joke books.

Asked whether they've yet succumbed to the lure of artificial intelligence, Ms Harris responds with a firm denial.

She says the aim of the session is to work out what their favourites were and which delivered the greatest emotional reaction.

"Does it do what we want around the Christmas table?" she asks.

Chloe Lloyd, from the sales team, pitches a joke she has heard earlier that day.

"What does the moon do when it needs a haircut?," she asks. 'Eclipse it!"

That's an instant hit, the group says.

Gathering to enjoy shared laughter is not only nothing new, experts say, it is likely to be pre-human.

Laurence Cawley/BBC

Laurence Cawley/BBC

Laughing at a cracker joke is about forging and cementing social bonds, says Prof Sophie Scott

"So when you are laughing with people around the Christmas table you are dropping into what's almost certainly a really ancient mammal play vocalisation," says Prof Sophie Scott, the director of University College London's Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience.

Shared laughter, she says, helps make and maintain social connections between people.

Researchers have found the lack of such interactions can seriously damage mental and physical health.

"The people you talk to, and laugh with, it leads to enhanced levels of endorphin uptake," says Prof Scott.

Endorphins are the brain's "happy chemicals" and are released both to reduce stress and pain and in response to pleasurable experiences, such as laughing with friends over a truly terrible Christmas cracker joke.

"You're not just laughing at a silly joke with a Christmas cracker," Prof Scott says. "You are actually doing a lot of the really important work of making, maintaining the social bonds you have with those you love."

And it is not just humans that laugh.

Laughing, says Prof Scott, is an invitation to play and build social bonds. Rats and a number of other mammals do it too.

Laurence Cawley/BBC

Laurence Cawley/BBC

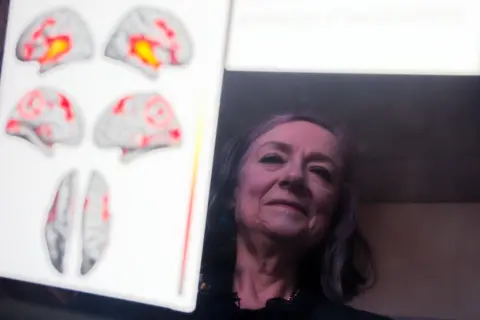

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, a type of brain scanner, Prof Scott and her team have been able to map the areas of the brain that receive more blood

But what is actually happening inside the brain when we hear a joke?

An awful lot happens in response to humour, it turns out.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a type of brain scanner which shows which parts of the brain are working harder, Prof Scott and her team has been able to map the areas that receive more blood.

Testing involves scanning the brains of healthy participants and then subjecting them to a database of funny words, accompanied by either a neutral "crunchy" noise, or pre-recorded laughter, and to then examine which parts of the brain are working hardest.

"In the scanner we got a really interesting pattern of activation," says Prof Scott.

A joke activates not just the parts of the brain responsible for hearing and interpreting speech, but also brain areas involved in both planning and initiating movement and those involved in vision and memory.

Put all of this together, says Prof Scott, and people hearing a joke have a complex set of neural responses that underpin the laughter we hear - they not only listen to and understand the joke, but prime the motor functions needed to prepare to laugh, and have their response influenced by images from memory.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Neuroscientists say their research has found laughter itself is contagious and releases "feel-good" chemicals in the body

Researchers discovered that when a funny word is paired with laughter there is a greater response in the brain than the same word when followed by a neutral sound.

"This was in parts of the brain that you would use to move your face into a smile or a laugh," Prof Scott says.

It means people are not just responding to funny words or jokes, they are responding to the laughter that accompanies them.

Laughter, says Prof Scott, can be contagious.

So what does this mean for the laughter found around a Christmas table?

"You laugh more when you know people," says Prof Scott, "and you laugh more when you like them or love them."

When it comes to Christmas cracker jokes, she says, the feel-good factor is more likely to be caused not by the joke itself, but from the response to it.

"It's the laughter. The joke is the terrible Christmas cracker joke, and it's just a reason to laugh together."

Will we ever discover the perfect joke?

Probably not, but that has not stopped experts from trying to.

In 2001 Prof Richard Wiseman, of the University of Hertfordshire, in Hatfield, set up LaughLab, the scientific search for the world's funniest joke.

More than 40,000 jokes later, with ratings lodged on those jokes by 350,000 people around the world, Prof Wiseman has a better idea than most as to what works and what does not.

The perfect Christmas cracker joke needs to be short, he says.

"But they also need to be poor jokes, jokes that make us groan," Prof Wiseman adds.

The more "terrible" the joke, he says the better.

"This is because if no-one laughs – it's the joke's fault, not yours.

"What's interesting about the Christmas cracker jokes is that none of us find them funny.

"That's a shared experience around the table and I think it's lovely."

More from London and East Investigations

3 hours ago

3

3 hours ago

3