Georgina Rannard

Climate and science reporter

Getty Images

Getty Images

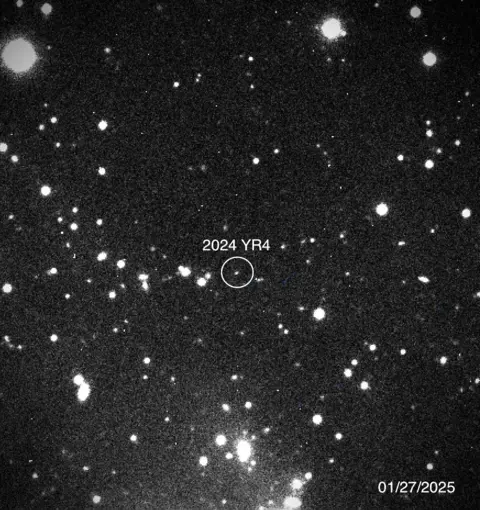

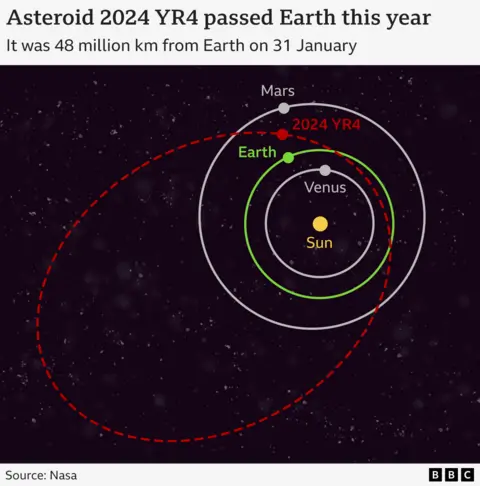

A large asteroid known as 2024 YR4 has grabbed headlines this week as scientists first raised its chances of hitting earth, then lowered them.

The latest estimate says the object has a 0.28% chance of hitting Earth in 2032, significantly lower than the 3.1% chance earlier in the week.

Scientists say it is now more likely to smash into the Moon, with Nasa estimating the probability of that happening at 1%.

But in the time since 2024 YR4 was first spotted through a telescope in the desert in Chile two months ago, tens of other objects have passed closer to Earth than the Moon, which in astronomical terms sounds like a near miss.

It is likely that others, albeit much smaller, have hit us or burned up in the atmosphere but gone unnoticed.

This is the story of the asteroids that you never hear about – the fly-bys, the near-misses and the direct hits.

The vast majority are harmless. But some carry the most valuable clues for unlocking mysteries in our universe, information we are desperate to get our hands on.

Drs. Bill and Eileen Ryan, Magdalena Ridge Observatory 2.4m Telescope, New Mexico Tech

Drs. Bill and Eileen Ryan, Magdalena Ridge Observatory 2.4m Telescope, New Mexico Tech

2024 YR4 was first detected in December and there is small chance it could hit Earth on 22 December 2032

Asteroids, also sometimes called minor planets, are rocky pieces left over from the formation of our solar system about 4.6 billion years ago.

Rocks routinely orbit close to Earth, pushed by the gravity of other planets.

For most of human history, it has been impossible to know how close we have come to being struck by a large asteroid.

Serious monitoring of objects near Earth only started in the late 20th century, explains Professor Mark Boslough from the University of New Mexico. "Before that we were blissfully oblivious to them," he says.

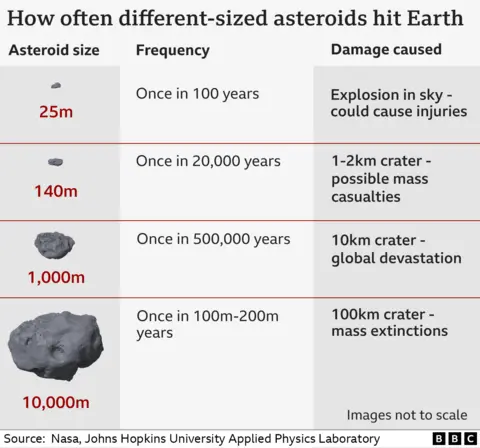

We now know that quite large objects - 40m across or more - pass between Earth and the Moon several times a year. That's the same size of asteroid that exploded over Siberia in 1908 injuring people and damaging buildings over 200 square miles.

The most serious near-miss, and the closest comparison with YR4, was an asteroid called Apophis which was first spotted in 2004 and measured 375 meters across, or around the size of a cruise ship.

Professor Patrick Michel from French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) tracked Apophis and recalls it was considered the most hazardous asteroid ever detected.

It took until 2013 to get enough observations to understand that it was not going to hit Earth.

But he says there was one big difference with YR4. "We didn't know what to do. We discovered something, we determined an impact probability, and then thought, who do we call?" he says. Scientists and governments had no idea how to respond, he says.

A large asteroid strike could be catastrophic if it hits an area where humans live.

We don't know exactly how big YR4 is yet, but if it is at the top end of estimates, about 90m across, it would likely remain substantially intact rather than break up as it enters the Earth's atmosphere.

"The surviving asteroid mass could create a crater. Structures in the immediate vicinity would likely be destroyed and people within the local region (dozens of kilometers) would be at risk of serious injury," explains Professor Kathryn Kunamoto from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Some people could die.

But since Apophis, there have been huge advances in what is called planetary defence.

Prof Michel is part of the international Space Mission Planning Advisory Group.

Its delegates advise governments on how to respond to an asteroid threat and run rehearsal exercise for direct hits. There is one going on right now.

If the asteroid was on course for a town or city, Dr Boslough compares the response to preparations made for a major hurricane, including evacuations and measures to protect infrastructure.

The Space Mission Planning Advisory Group will meet again in April to decide what to do about YR4.

By then most scientists expect the risk to have almost entirely gone, as their calculations of its trajectory become more precise.

We do have options beyond "taking a hit", as Dr Kumamoto puts it.

Nasa and the European Space Agency have developed technologies to nudge dangerous asteroids off course.

Nasa's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) successfully slammed a spacecraft into the asteroid Dimorphos to change its path.

However scientists are sceptical if that would work in the case of YR4 due to uncertainty about what it is made of and the short window of time to successfully deflect it.

And what about the asteroids that do hit Earth? An awkward truth for scientists is that a direct strike on land far from humans is the ideal scenario for asteroids.

That gives them actual pieces from distant objects within of our solar system, as well as insights into Earth's impact history.

Nearly 50,000 asteroids have been found in Antarctica. The most famous, called ALH 84001, is believed to have originated on Mars and contains minerals with vital evidence about the planet's history, suggesting it was warm and had water on its surface billions of years ago.

In 2023 scientists detected an asteroid called 33 Polyhymnia which could have an element denser than anything found on Earth.

This superheavy element would be something entirely new to our planet. 33 Polyhymnia is at least 170 million kilometers away, but it's an indication of the incredible potential of asteroids for our understanding of science.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The Barringer Crater in Arizona, US was formed by a meteorite about 50m across that hit 50,000 years ago

Now that the chances are higher that YR4 will hit the Moon, some scientists are getting excited about that.

An impact could give real-world answers to questions they have only been able to simulate using computers.

"To have even one data point of a real example would be incredibly powerful," says Prof Gareth Collins from Imperial College London.

"How much material comes out when the asteroid hits? How fast does it go? How far does that travel?" he asks.

It would help them test the scenarios they have modelled about asteroid impacts on Earth, helping create better predictions.

YR4 has reminded us that we live on a planet vulnerable to collisions with something the solar system is full of – rocks.

Scientists warn against complacency, saying it is a matter of when, not if, a large asteroid will threaten human life on Earth, although most expect that to be in the coming centuries rather than decades.

In the meantime, our ability to monitor space keeps improving. Later this year the largest digital camera ever built will begin working at the Vera Rubin Observatory in Chile, able to capture the night sky in incredible detail.

And the closer and longer we look, the more asteroids spinning close to Earth we are likely to spot.

3 months ago

95

3 months ago

95