Sadaf GhayasiBBC Afghan Languages

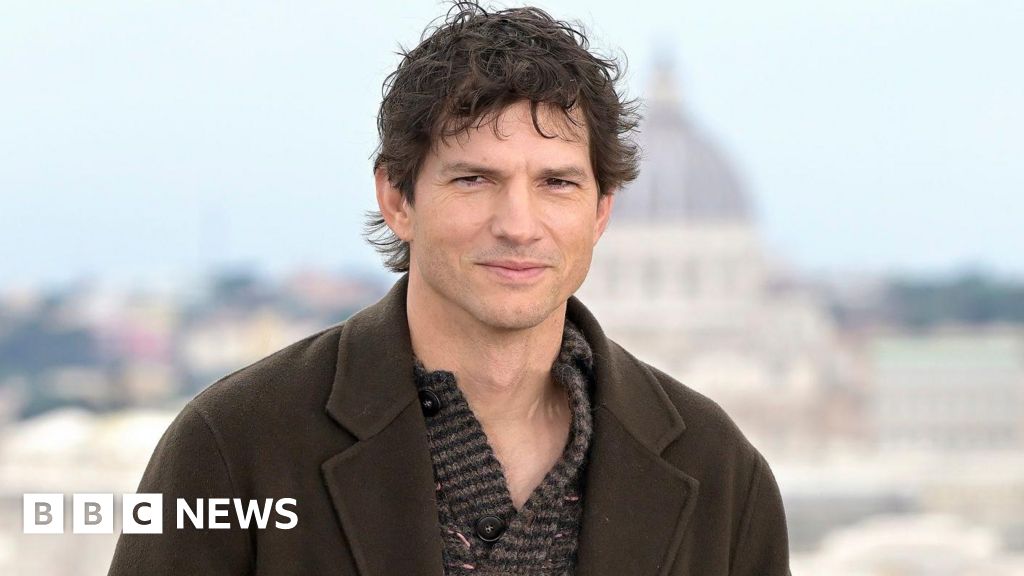

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee is worried that a generation of Afghan children is at risk of being radicalised

Maiwand Banayee now lives a relatively unremarkable life.

When the 45-year-old isn't working with the National Health Service supporting people with diabetes, or studying for his postgraduate degree, you'll likely find him lifting weights at his local gym in Coventry.

But his comfortable life in the Midlands is a far cry from the 1990s, when he says his "only desire was to die as a martyr" fighting for the Taliban, even if that involved taking part in a suicidal mission.

Mr Banayee says he eventually managed to pull himself away from the extreme jihadism of the Taliban and has written a book, Delusions of Paradise: Escaping the Life of a Taliban Fighter, which he hopes will prevent others becoming radicalised.

In it, he explains how he was lured by the promise of glory and that he came to believe a direct route to paradise was to sacrifice his life fighting for "a pure Islamic society".

Now he is worried that, since the Taliban's return to power in 2021, a "rapid increase in religious schools in Afghanistan" is exposing a new generation of children to extremism.

Born in Afghanistan in 1980, Maiwand Banayee was the youngest son in a Pashtun family.

"To my father's disappointment, I was a soft and sensitive kid. The neighbourhood gang of kids bullied me, and my father and adult brother scorned me for not fighting back," he remembers.

But in 1994, at the age of 14, Mr Banayee says he found himself being radicalised by jihadists in the Shamshato refugee camp in Pakistan. He had fled Kabul with some of his siblings, due to the Afghan civil war. His parents joined them later.

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee at the age of 14 in Shamshato camp after he fled his home in Kabul

Life at the camp was tough, Mr Banayee remembers, with few home comforts and intense religious propaganda. He says the day would start with Quran recitals at dawn, followed by lessons at a madrassa - religious school - and preaching sessions at the mosque.

In the madrassa, he recalls mullahs - Muslim clerics - preaching heavily on a specific topic - martyrdom.

"They told us that the world had become infidel and godless, and only martyrdom would take a person to heaven," he says. "The conditions were very ripe for extremism."

He recalls being told by the Pakistani mullahs - who he thinks were more political and more extreme than those he had encountered in Afghanistan - that Muslims must prevail so that hardship would not overwhelm them.

"They prepared you to kill and to sacrifice yourself," he says, adding that before long, this fetishisation of death began to take hold on him.

He describes how the mullahs offered erotic descriptions of the afterlife, promising beautiful virgins "a million times more beautiful than women on Earth" with "large breasts, white skin and seductive lips… and after each sexual encounter they would become virgins again".

These promises had a profound psychological impact on the teenagers, he says.

"We were hungry, poor, sexually repressed and powerless. These promises were like hope for us," Mr Banayee says.

"I had internalised these beliefs. I had convinced myself that the afterlife was better and that I desired it."

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee

Shamshato camp after Friday prayers in 1997

Mr Banayee says that he felt increasingly vulnerable and helpless in Shamshato. The camp had originally been established in 1983 to house Afghan refugees fleeing the Soviet invasion.

It was dominated by the Islamist Hezb-e-Islami group, headed by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar.

Over the years, Hekmatyar - and other Afghan mujahideen leaders - received US funds as they used madrassas to recruit people to resist Soviet forces.

But after the Soviets left in 1989 and Afghanistan fell into civil war, Hekmatyar's influence in Shamshato remained.

After a couple of years there, in 1996, Mr Banayee says he left the camp and returned to Kabul, where the Taliban had emerged and taken control of most of Afghanistan, including the capital. The group enforced an austere version of Sharia law that aligned with what he had been taught in Pakistan.

In their first regime, the Taliban banned television, music and cinema, barred girls from school, forced women to wear the all-covering burka and men to grow beards. The Taliban also introduced public executions for convicted murderers and punished thieves by amputating a hand.

Banayee says he joined the Taliban, and while he didn't fight, he promoted their propaganda and enforced Taliban laws, carrying a weapon at all times.

"My entire life, I had struggled with doubts about my masculinity and a suppressed desire to be seen as brave," he says. "Now that I carried a gun on my shoulder, I felt as though the world was under my feet. Every day, I put on a huge silk turban, picked up my gun, and roamed around the village as if I owned the Earth."

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee

Maiwand Banayee, sitting bottom right, in Afghanistan when he was a member of the Taliban

He recalls once coming home to find that his parents had bought a black-and-white TV, and his sisters were watching it.

"I smashed the TV and clashed with my father," he says. "They told me I had gone mad - that my extremism had gone too far. They couldn't understand why I was so against the TV.

"I was a young man who had been taught by the mullahs in the madrassa that when your mothers and sisters watch TV and see clean-shaven men, they become attracted to them and want to sleep with them."

Mr Banayee says he was waiting for a call to fight soldiers loyal to Ahmad Shah Massoud, a former mujahideen commander who had fought the Soviets and was now resisting the Taliban in northern Afghanistan. Massoud was later killed by an al-Qaeda suicide squad in 2001, two days before the 9/11 attacks on New York.

"My only dream was to go to the north and be martyred," he says.

But after a few months in the Taliban, Mr Banayee says he started to question the path he was on. He travelled back to Pakistan, hoping to enrol in the Darul Uloom Haqqania madrassa, referred by some as the "University of Jihad" due to some of its alumni, but there were no available spaces.

Disappointed, he returned to Afghanistan in 1997. On his way back to Kabul, he recalls an incident that left a lasting impression on him.

Shortly after praying, he says, Taliban fighters stopped him and ordered him to pray again.

"I told them I had just done so, but they didn't care. They threatened to hit me with their guns if I didn't obey. It felt wrong, so disrespectful. I was 17, my ego was hurt. I thought, 'I love the Taliban so much, but is this how they treat me?'"

He also remembers seeing public executions at Kabul's Ghazi Stadium, originally built for sport and public events, which the Taliban frequently used for punishments and executions.

"They cut off hands. I closed my eyes. Then someone was forced to shoot his brother's killer," he recalls. "That was the moment I started doubting: 'If these people represent Islam, why is there so much cruelty?'"

Stefan Smith/AFP via Getty Images

Stefan Smith/AFP via Getty Images

After the Taliban came to power in 1996, they carried out punishments including public executions, floggings and amputations in the stadium in Kabul

The next few years were spent moving between Pakistan and Afghanistan where he says he was mostly attending religious schools, making bricks and selling vegetables. In Shamshato, he remembers frequent clashes between Pakistani police and young men undergoing religious training.

Eventually, Mr Banayee says he left in 2001 due to rumours spreading that the police would raid the camp and he was afraid he would be arrested. He travelled through Russia and Dubai and then on to the UK, where, he says, his asylum application was rejected in 2002.

He describes sleeping in parks and public telephone boxes at night in Cardiff. One night, he says immigration police came to the door of a house where he was staying, but he evaded arrest by hiding under a bed.

After two years, in 2004, Mr Banayee says he went to Ireland, which also rejected his claim for asylum.

But while he was there, he met an Irish woman - he says they fell in love and married.

Marrying an Irish person does not give someone an automatic right to live in Ireland - each case is assessed individually. Mr Banayee was allowed to stay and later became an Irish citizen.

In 2023, he moved to Coventry, where he still lives and works with the NHS as a diabetes remission coach. He and his wife split up two years ago, but they have a 17-year-old daughter who is still at school.

"She is proud of me, she knows everything," he says of his daughter.

Terence White/AFP via Getty Images

Terence White/AFP via Getty Images

The Afghan civil war that uprooted Mr Banayee led many others in Kabul to flee their homes too

He says that deradicalising was a very gradual process. "Indoctrination takes time to settle," he adds. "Similarly, coming out of that mindset isn't something that happens in a flash."

Mr Banayee describes it as a "long, slow unravelling".

"Each doubt was a small crack," he recalls. "Together, they hollowed me out."

He feels his past still affects his life today and his teenage dream of martyrdom is now a nightmare that haunts him.

"It was a different world, it was difficult to find my way between two completely different cultures.

"The difference drove me and my ex-wife apart. What you experience in the past always affects your present and future."

But Mr Banayee is aware his life could have taken a far darker path, and says many of the people he knew in Afghanistan are still in extremist circles.

"Some of my classmates in the religious school became suicide bombers and killed themselves and others. I changed, but they didn't," he says, explaining that in some ways he sees them as victims, targeted and used by Islamist militants in the region.

The last time he went back to Afghanistan was in 2019, but he thinks the criticism he has included in his book makes it too dangerous for him to visit again, now that the Taliban are back in power.

And his message for young people at risk of being radicalised? Question everything.

"I was searching for meaning and spirituality in life, and I saw all of that in that path," he says. Mr Banayee says he absorbed all kinds of myths, believing that the body of a martyr would not rot and that birds would warn Muslims of incoming bomber aircraft.

Eventually, he came to question the lessons he'd been taught. "None of them were true."

3 months ago

90

3 months ago

90