Ben Chu & Tom Edgington

BBC Verify

Getty Images

Getty Images

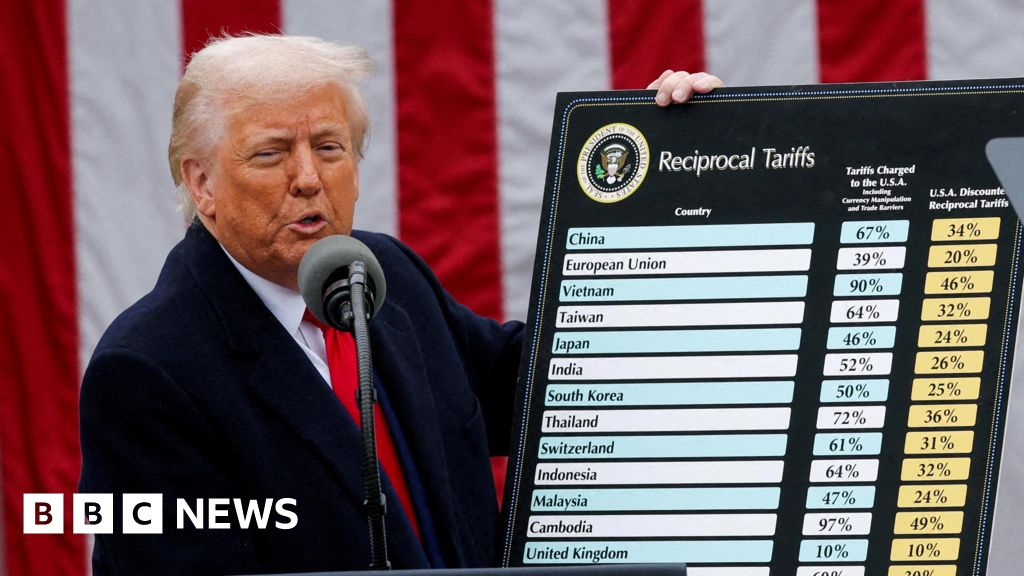

US President Donald Trump has imposed a 10% tariff on goods from most countries being imported into the US, with even higher rates for what he calls the "worst offenders".

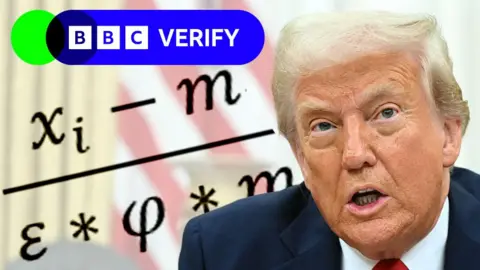

But how exactly were these tariffs - essentially taxes on imports - worked out? BBC Verify has been looking at the calculations behind the numbers.

What were the calculations?

White House

White House

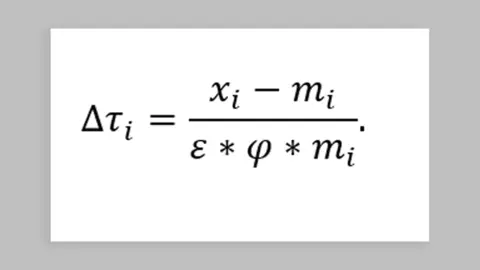

The formula shared by the White House

Are the Trump tariffs 'reciprocal'?

Many commentators have pointed out that these tariffs are not reciprocal.

Reciprocal would mean they were based on what countries already charge the US in the form of existing tariffs, plus non-tariff barriers (things like regulations that drive up costs).

But the White House's official methodology document makes clear that they have not calculated this for all the countries on which they have imposed tariffs.

Instead the tariff rate was calculated on the basis that it would eliminate the US's goods trade deficit with each country.

Trump has broken away from the formula in imposing tariffs on countries that buy more goods from the US than they sell to it.

For example the US does not currently run goods trade deficit with the UK. Yet the UK has been hit with a 10% tariff.

In total, more than 100 countries are covered by the new tariff regime.

'Lots of broader impacts'

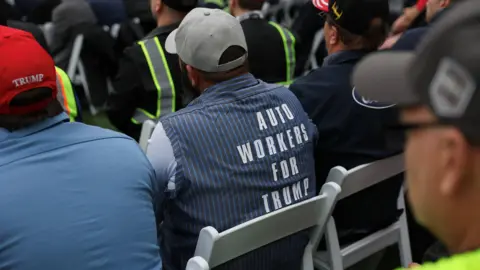

Trump believes the US is getting a bad deal in global trade. In his view, other countries flood US markets with cheap goods - which hurts US companies and costs jobs. At the same time, these countries are putting up barriers that make US products less competitive abroad.

So by using tariffs to eliminate trade deficits, Trump hopes to revive US manufacturing and protect jobs.

Reuters

Reuters

The US car industry is one of the manufacturing sectors Trump is keen to revive

But will this new tariff regime achieve the desired outcome?

BBC Verify has spoken to a number of economists. The overwhelming view is that while the tariffs might reduce the goods deficit between the US and individual countries, they will not reduce the overall deficit between the US and rest of the world.

"Yes, it will reduce bilateral trade deficits between the US and these countries. But there will obviously be lots of broader impacts that are not captured in the calculation", says Professor Jonathan Portes of King's College, London.

That's because the US' existing overall deficit is not driven solely by trade barriers, but by how the US economy works.

For one, Americans spend and invest more than they earn and that gap means the US buys more from the world than it sells. So as long as that continues, the US may continue to keep running a deficit despite increasing tariffs with it global trading partners.

Some trade deficits can also exist for a number of legitimate reasons - not just down to tariffs. For example, buying food that is easier or cheaper to produce in other countries' climates.

Thomas Sampson of the London School of Economics said: "The formula is reverse engineered to rationalise charging tariffs on countries with which the US has a trade deficit. There is no economic rationale for doing this and it will cost the global economy dearly."

20 hours ago

6

20 hours ago

6