Dominic Casciani,Home and Legal Correspondentand Daniel Wainwright,Senior data journalist, BBC Verify

Getty Images

Getty Images

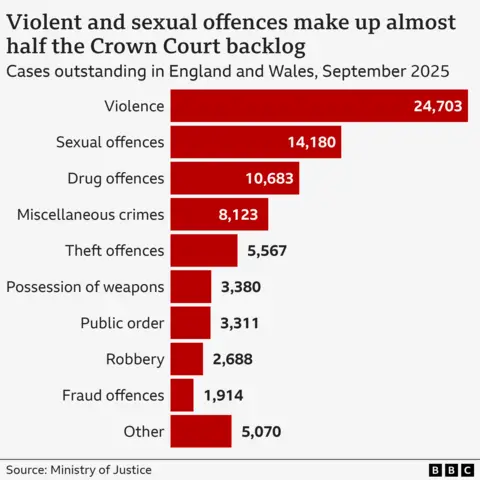

More than 79,600 criminal cases are now caught in the courts backlog in England and Wales, new figures show.

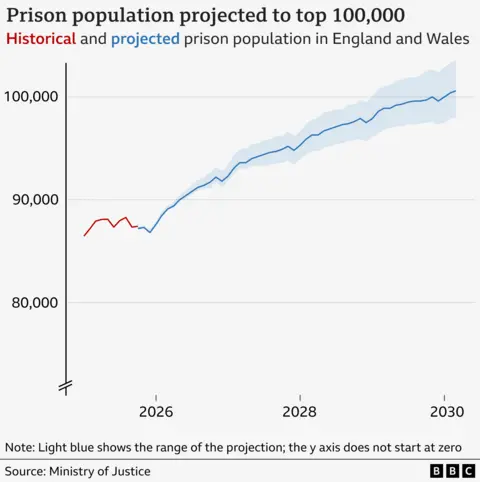

The Crown Court backlog has been at a record high since early 2023 and is projected to hit 100,000 by 2028, according to the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). The delays mean that for some serious crimes charged today the victims and suspects could be left waiting years for justice as they are unlikely to see the case come to trial before 2030.

This crisis has prompted the government to announce radical reforms to the criminal courts, including removing juries - a fundamental part of our criminal justice system - from a number of trials in England and Wales in an attempt to speed up justice and slash the backlog.

The latest MoJ figures show there has been a huge growth in cases taking two years or more to conclude, something that was a rarity before 2010 budget cuts began to bite, and which was later exacerbated by the pandemic and other factors.

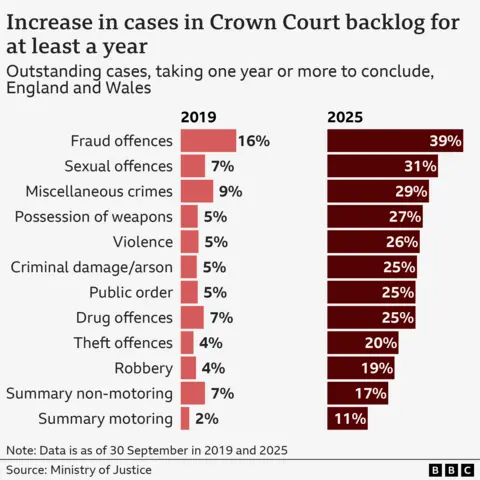

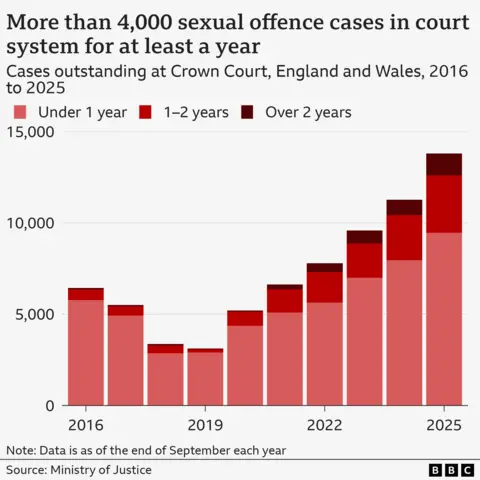

About a quarter of violence and drug offences, many of which do not require the defendant to be detained pre-trial, have been in the backlog for at least a year. More than 30% of sexual offences have been in the system for at least that long. For context, in 2019 there were around 200 sexual offences that had been open for more than a year. Now there are more than 4,000.

It means the situation has become significantly worse for victims, defendants, witnesses and everyone else who works in the system, and shows the scale of the problem the government is now grappling with.

So how did we get here? At the heart of this story is funding - and the lack of it - which started in 2010.

Back then the coalition government pledged to slash spending to balance the books - and the MoJ took a huge cut to its £9bn budget. It means its total spending today is £13bn, which is £4.5bn lower in real terms than it would have been had it kept pace with the average government department, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies.

Why did that cut happen?

When the coalition government began making austerity cuts, the MoJ took a bigger hit than some other departments such as health and defence. It delivered some of its cuts by shutting court rooms, and by 2022, eight crown court centres and more than 160 magistrates courts were gone, according to ministerial answers to parliamentary questions.

Ministers also introduced a cap on the number of days judges are paid to sit in court and hear cases, to help reduce spending.

In 2016-17 there were 107,863 of these "sitting days" recorded, but that had fallen to 81,899 by the eve of the pandemic. If there's no judge, there's no hearing, which meant individual courtrooms were left idle even if the rest of a court complex was still hearing cases.

Then the Covid pandemic happened, which left all Crown Courts closed for two months during the first lockdown other than for urgent and essential work. When they reopened, many individual courtrooms could not be used for trials because they were too small to comply with social distancing requirements. Everything slowed to a snail's pace and the backlog exploded.

This is when the unintended consequences of earlier closures began to bite harder. Take for example Blackfriars Crown Court in London. Its nine court rooms were once an important centre for serious organised crime cases, but ministers decided to close it in 2019 and hoped to sell the land.

Many of its cases were shifted to Snaresbrook in east London, but since the pandemic it has been overwhelmed. At the end of September 2019 it had 1,500 cases on its books, official figures show, but as of September this year it was juggling more than 4,200.

Before the pandemic, only 5% of outstanding cases for violence across England and Wales had been in the system for more than a year - now a quarter of cases have taken that long. There have been similar increases in the length of time taken for criminal damage, possession of weapons and drug offence cases.

During the Covid pandemic, temporary "Nightingale courts" were introduced to help alleviate pressure on the court system by keeping some cases moving, sitting for 10,000 days between July 2020 and 2024.

But they could not deal with serious crime involving custody because they were often in conference centres or hotels with no cells or appropriate security. Today there are still five Nightingale courts operating, all of which are due to close by March 2026.

Sometimes the MoJ re-opened a court it had closed. Chichester's Crown Court was shut down, despite local opposition, in 2018. It was temporarily re-opened to help deal with the overflow of cases from Guildford 40 miles away - and its future remains uncertain, despite the backlogs.

Getty Images

Getty Images

David Lammy has announced radical reforms to the courts system

But there is another element that has made everything much harder to fix.

The national legal aid system pays for barristers and solicitors to act for a defendant who cannot afford to pay for their own lawyer. It both helps ensure a fair trial and keeps cases moving through the courts, but the funding for this system has been repeatedly cut or frozen over the past 25 years, which in turn has led to a fall in barristers taking criminal cases.

The National Audit Office found there has been a real term reduction in legal aid spending by the MoJ of £728m between 2012-13 and 2022-23.

And there has also been a 12% fall in the number of barristers doing criminal work between 2018-19 and 2024-25, according to the Criminal Bar Association.

In 2021, the government was advised to inject £135m extra funding into legal aid but it did not go far enough for many in the profession and triggered months-long strike action from defence barristers the following year. This created a second wave of chaos in the courts because, just like in the pandemic, cases could not progress through the system.

The shortages in judges and lawyers contrast sharply with what happened to policing. In 2019 former prime minister Boris Johnson promised to hire 20,000 extra police officers across England and Wales, reversing the fall that began during austerity cuts. That meant more suspects charged and sent to trial - but critics said there was no corresponding planning for how this would impact the courts.

Prosecutions can also take longer because of changes to how evidence is gathered by police, particularly involving our digital lives. Many cases today, especially those involving serious sexual offences, involve a huge amount of evidence taken from digital sources such as mobile phone chats, which can take months to comb through ahead of a trial and more time going through it with a jury.

The backlog also has a knock-on effect on prisons. There are nearly 17,700 people on remand in England and Wales, almost double the number in 2019 . This includes people who have been convicted of a crime but have not yet been sentenced, and nearly 12,000 people who are waiting for a trial.

People held on remand accounts for around 20% of the prison population. The number of prisoners in England and Wales is already projected to top 100,000 by 2030 according to the MoJ.

That crisis led Sir Keir Starmer's governent to introduce an early release scheme for some offenders last year and pledge wider justice reforms.

If people on remand don't have their cases completed then they can't be released or sent to serve a sentence, which means prisons will quickly fill up again. But while the courts try to prioritise remand cases at the expense of everyone else entering the system, the growing queue of cases has become ever longer.

2 months ago

81

2 months ago

81