Ryan O'HanlonJun 13, 2025, 07:52 AM ET

- Ryan O'Hanlon is a staff writer for ESPN.com. He's also the author of "Net Gains: Inside the Beautiful Game's Analytics Revolution."

Are you or a loved one "getting Concacafed?"

Are you experiencing symptoms of a referee giving you a yellow card for getting punched by another player? Have you felt confusion upon watching another man somersault across the grass in anguish after you shook his hand to congratulate him on a nice play? Ever seen a group of ball boys shrug their shoulders and sit, immobile, after a goalkeeper literally punted the ball into the Atlantic Ocean? Want to scream because you just lost a game on a field of knee-high grass against a team of players who spent most of the past week on a commercial fishing boat?

If you've followed North American soccer for long enough, you're familiar with the term. Heck, ESPN contributor Jon Arnold writes an entire newsletter about it every week; it's called Getting CONCACAFed.

Arnold's newsletter celebrates the conundrum that is Concacaf -- a region that features two of the richest federations in all of the sport, the United States and Mexico; another one that mostly plays hockey, Canada; and then a bunch of other soccer-loving nations with varying (low) levels of resources and degrees of professionalism. Just a few years ago, the 60-year-old president of Suriname forced himself into a Concacaf league match. This is the same federation within which Lionel Messi plays his club ball and the likes of Christian Pulisic and Alphonso Davies represent their countries. It all exists together, and it's beautiful.

At its worst, though, the fans who talk about getting Concacafed are fans of the richest country in the region, and they're complaining about the "uncultured methods" of their poorer regional brethren. God forbid the underdogs try to find ways to even the playing field.

But what actually happens in Concacaf, from minute one through 90? It's a question with competitive consequences in the Gold Cup, which begins Saturday, for the U.S. men's national team, Mexico and Canada -- all of whom also hope to make it deep into next summer's World Cup.

How different is the sport played here, compared with over there? Let's look into the numbers.

Physicality

We'll start with the place where it seems Concacaf is most different from everywhere else: its apparent tolerance for violence.

In the rest of this piece, we'll be comparing the Gold Cup with the Copa América, the Euros and the Premier League. Because there aren't many games in any one international tournament, we're using data from the past two Gold Cups, Copas América and Euros. And then we're using only this past season of Premier League data, since there are way more games. This should give us a sense of how Concacaf stacks up against the two best regions for international soccer and then the gold standard for club soccer.

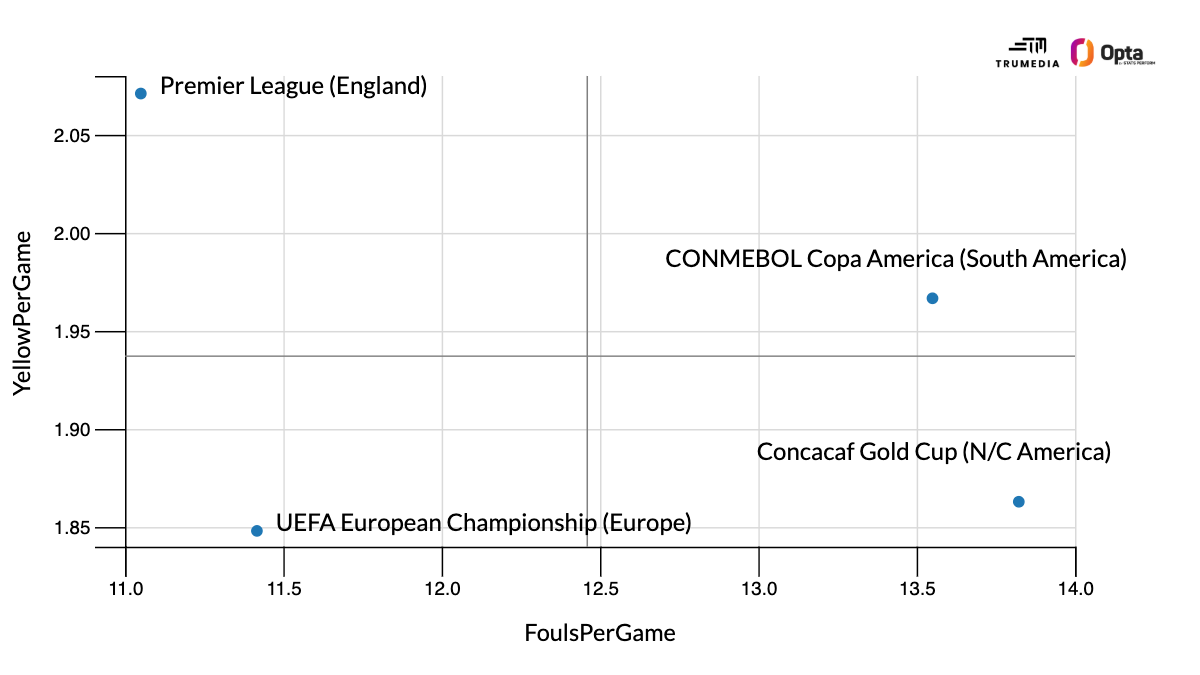

Here's a graph that plots the number of yellow cards per game and the number of fouls per game for the average team:

Though the Gold Cup averages more fouls per game than any of the three other competitions, it also averages the second-fewest yellow cards -- just barely more (1.86 per game to 1.85) than at the Euros.

The way I'd interpret this data: The Concacaf referees allow a lot more physicality than refs do in any of the other tournaments. Though the Copa América has a reputation for being one big rock fight, there aren't as many fouls as in North America, and the referees are way quicker on the draw with their yellow and red cards.

Passing

One of the themes here is that, stylistically, South American soccer has a lot more in common with North American soccer than it does with European soccer. Part of the reason for the similar data is that a few Concacaf teams played in last summer's Copa América, but that's not enough to skew the numbers much.

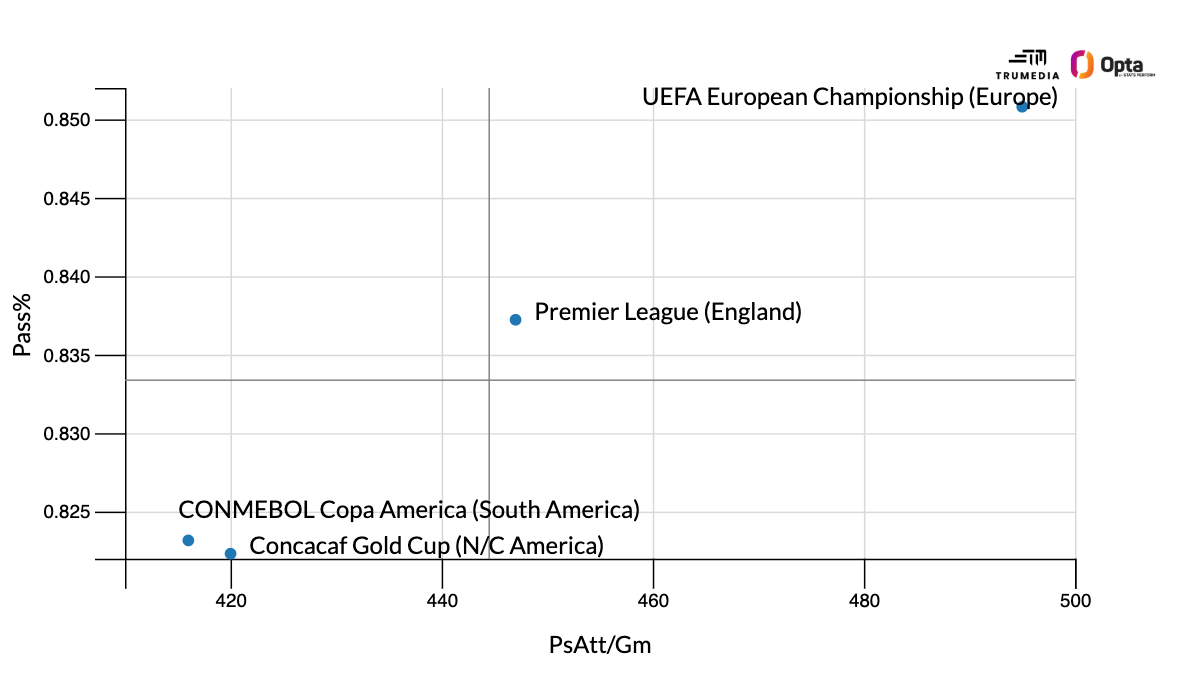

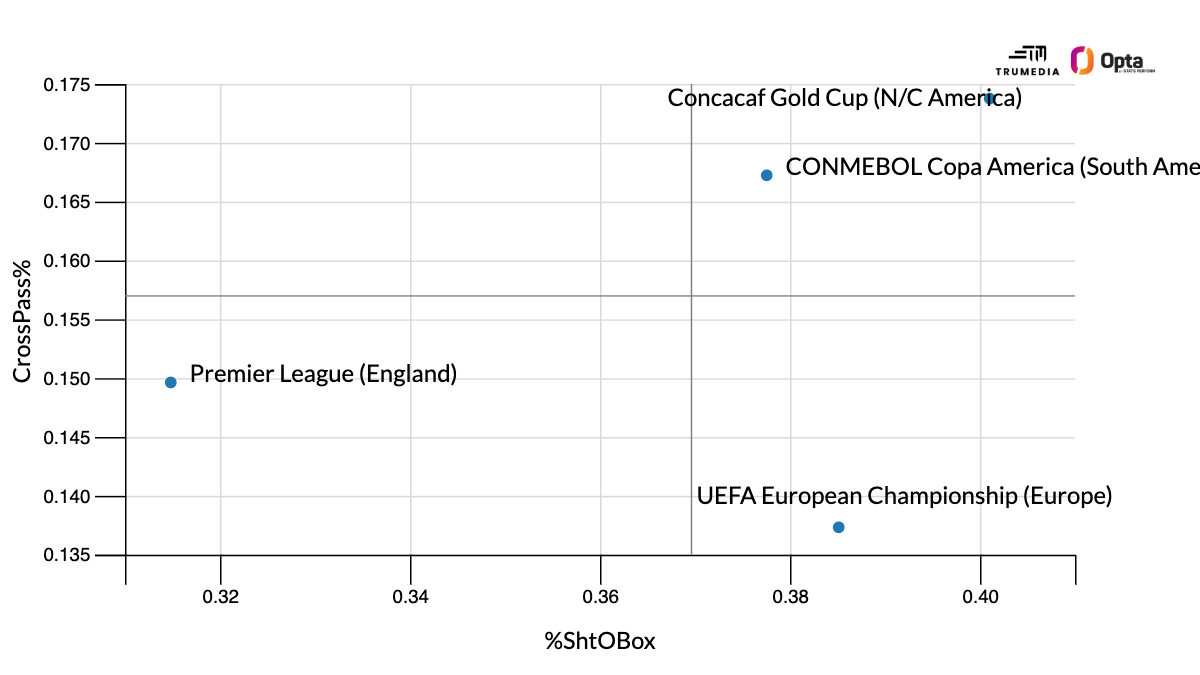

Now, take a look at our next graph:

Why are the Euros all the way in the upper right corner? The possession game is more prevalent in Europe, but in the Premier League, teams are coming up against much more athletic players and much more aggressive pressing systems than in the Euros. So, in the Euros, it's not that these teams are better at passing than Premier League clubs; it's just a lot easier to pass. Plus, both Euros in the dataset came at the end of long seasons, so teams tended to sit on the ball longer once they won possession.

However, the average Gold Cup team attempts around 420 passes per game and completes 82% of them. Those are, nearly exactly, the same numbers that relegated Leicester City put up in the most recent Premier League season.

Although the passing numbers are quite similar, the major area where Concacaf and CONMEBOL differ is in how often dribbles are attempted. Copa America teams attempt 21.2 take-ons per game -- the most of the four competitions we're looking at -- while Gold Cup squads try to beat their opponents on the dribble 17.7 times per game, second fewest in our dataset.

Aggression

This is where Concacaf sits on its own -- but not for the reasons you might think.

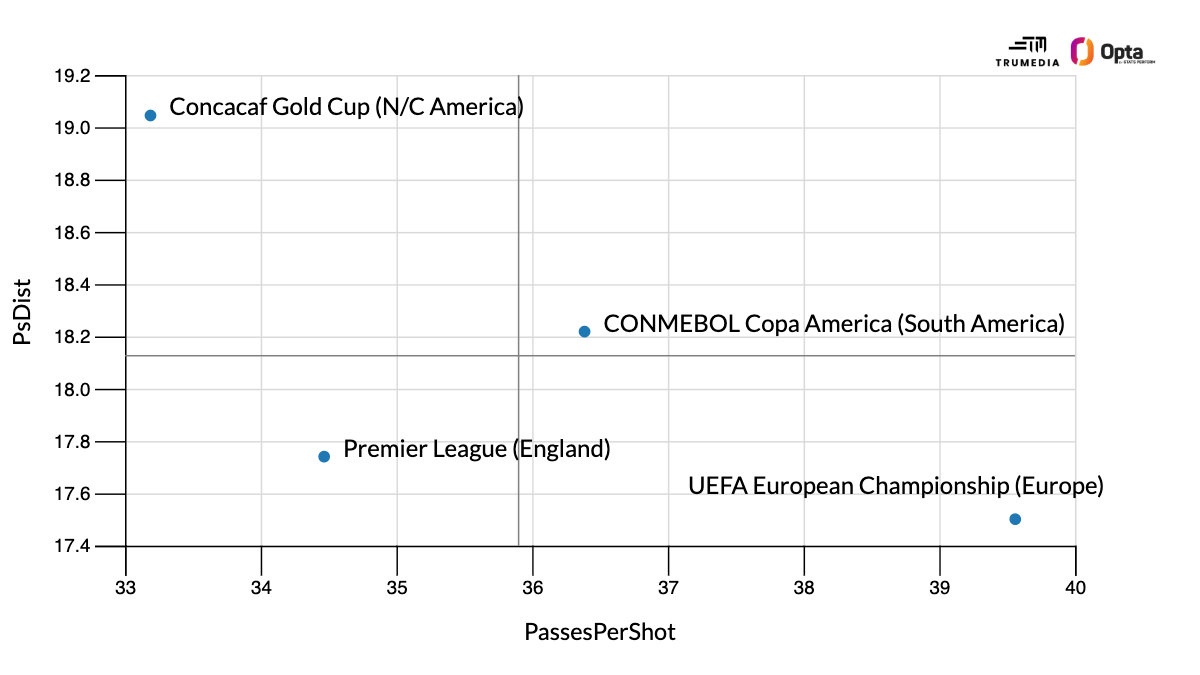

When I say "aggression" here, I don't mean, "How much do you try to injure your opponents?" Instead, I mean: "How aggressively are teams trying to move the ball forward?" There are two ways to determine that: How far do they pass the ball, and how many passes do they make before they attempt a shot?

Behold, the answer!

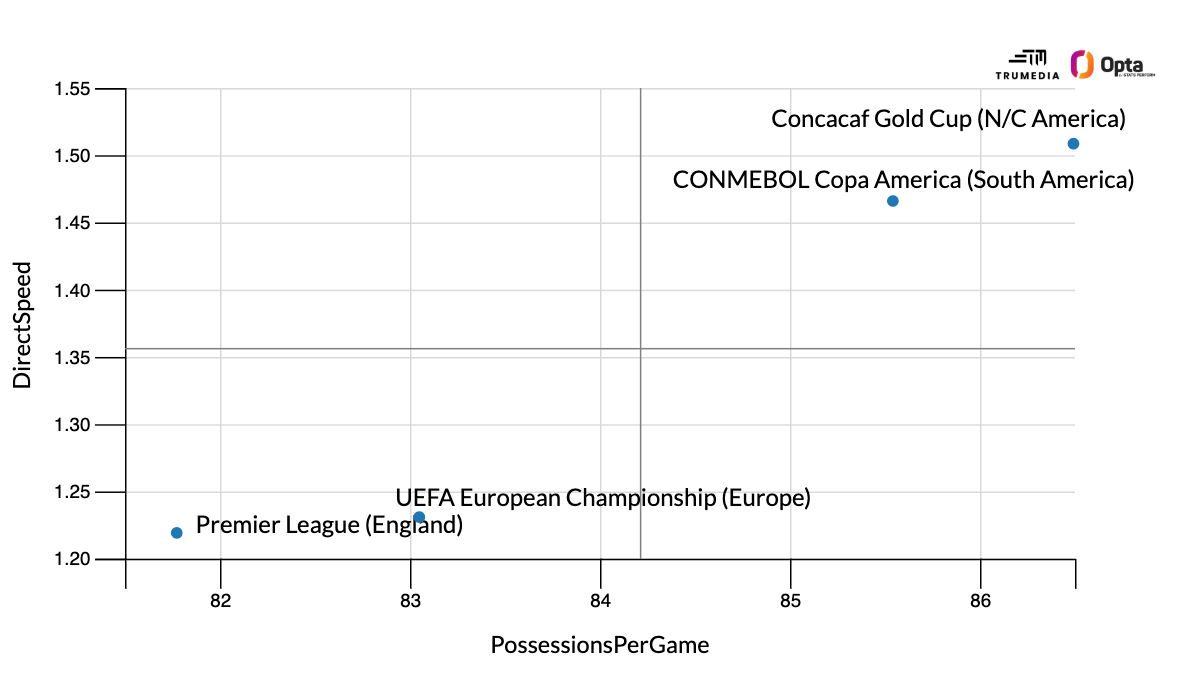

The longer passing and trigger-happy approach also leads to more moments of transition. In Concacaf, the ball changes hands more frequently (the number of possessions per game) and moves up the field more quickly than in the other competitions:

Those possession and speed numbers are almost exactly what Andoni Iraola's Bournemouth averaged this past season. Tyler Adams was born to play in this tournament --- and yet, he never has. Depending on how serious his foot injury is, it's possible he never will.

Shooting

All right, so we now know that there are lots of fouls and very few cards at the Gold Cup. We know there aren't many passes attempted, and there are even fewer completed. There's not much dribbling, either. But there's lots of long, aggressive passes, plenty of turnovers and a bunch of shots. Broadly, this is what Gold Cup games look like.

What about the shots themselves? We know how teams are getting the ball forward, what midfield play tends to look like, and how frequently shots are being attempted. But what kind of shots are these?

If there are two basic tactical takeaways from soccer's still-fledgling analytics movement, they are: (1) stop shooting from outside the box and (2) stop crossing so much. Now, this isn't to say you should never cross, but most crosses don't lead to shots; they lead to turnovers that leave your defense scrambling. And even when crosses lead to shots, those shots tend to be with your head, and headers are way less likely to turn into goals than shots with your feet.

As for point one, well, yeah, duh. The hallmark of every analytical revolution in sports was something obvious: For baseball players, getting on base is good, no matter how you do it; passing a football is easier than running; 3-point shots are worth more than 2-pointers; shots from close to the goal are more likely to go in.

Well, as of yet, it doesn't appear as if anyone has told anyone in Concacaf any of these things.

Paraguay or Albania players are used to seeing.

Paraguay or Albania players are used to seeing.

But in the Gold Cup, goals saved is right around expectation. The same kind of talent-level disparity doesn't exist in any kind of consistent way for keepers.

And then there's pressure on the ball. Perhaps because defenders in the other regions are more talented, or their tactics are more fine-tuned, or because possession play isn't so hectic, the Gold Cup averages the fewest shots under what Stats Perform defines as high pressure, but the most shots under either moderate or low pressure. Defensive pressure, or even the possibility of defensive pressure, has a large effect on shot conversion -- and there's just not as much of it in the Gold Cup, so we get more goals.

So what does it all mean?

I've written before about how the wide-open style of play in the German Bundesliga just isn't preparing Bayern Munich for the Champions League. Most teams in Germany aren't employing typical underdog strategies, so Bayern don't have to figure out how to break down low blocks. But they're also way more talented than everyone else in the league thanks to their massive resource advantage, so they're not playing games where they can't just expect to dominate the ball.

Then, in Europe, they play teams that challenge their claim to possession or fine-tune their own counterattacking strategies -- neither of which Bayern get any practice with at home.

There's probably some similar kind of translatability problem for the likes of the U.S., Mexico and even Canada. The soccer you see in Concacaf is just significantly different from what you'll see when you play in the World Cup, a tournament that theoretically gathers most of the best teams in the world. Plus, Concacaf is quite different from what all of the USMNT's best players experience on a week in, week out basis for their club teams in Europe these days.

The flipside of this is that the friendlies against European clubs better mirror the tactical environment the U.S. will be facing at the World Cup -- especially the first halves, when teams tend to be less experimental and at least enter the match with a cohesive lineup and some kind of plan. But, uh, yeah: Mauricio Pochettino's team has been outshot 17 to 4 -- to the tune of 0.14 expected goals for and 3.2 xG against; one goal for, six against -- across the two first halves of the recent Turkiye and Switzerland matches. This team is getting UEFAed, too.

Such is the nature of international soccer, then, that the sport the U.S. plays at the Gold Cup this summer will have only a vague connection to the sport it's going to play next summer. Also, the players playing this summer will only vaguely resemble the players who are playing next summer.

Given the recent performances, the latter is a positive. As for the former? It means we're unlikely to learn a whole lot from the Gold Cup about the team's chances at the World Cup. Given the trending direction of recent results, that's probably a good thing, too.