Vanessa ClarkeEducation reporter

Closing schools in Covid 'a nightmare idea', former PM Boris Johnson says

Papers in hand, Boris Johnson arrived at the Covid Inquiry before the sun came up.

He was there to answer questions on decisions he made during the pandemic that directly impacted children.

And what an impact they had.

School attendance, behaviour, screen time, speech and language - we now know the pandemic had an enduring effect on all of these issues for children.

Demand for speech and language support increased markedly after the pandemic. The amount of children who are persistently absent from school is still stubbornly high. And school suspensions and exclusions have hit record levels.

Each of these issues can be traced back to a part of the pandemic which has been central to this session of the inquiry: the closure of schools.

The decision to shut schools was one described by Boris Johnson on Tuesday as a "personal horror" for him, a "nightmare idea", but one which he also said seemed like the only option at the time.

We know that, in March 2020, the government was still maintaining an almost total focus on efforts to keep schools open.

But last week the former education secretary Gavin Williamson told the inquiry ministers should have "bitten the bullet" and done more to prepare for school closures.

We heard in earlier evidence given to the inquiry that there wasn't even a plan for the closure of schools until the day before it was announced on 18 March 2020.

This was described as an "extraordinary dereliction of duty" in the evidence of Sir Jon Coles, chief executive of the United Learning trust.

But on Tuesday, the former PM pushed back on that claim.

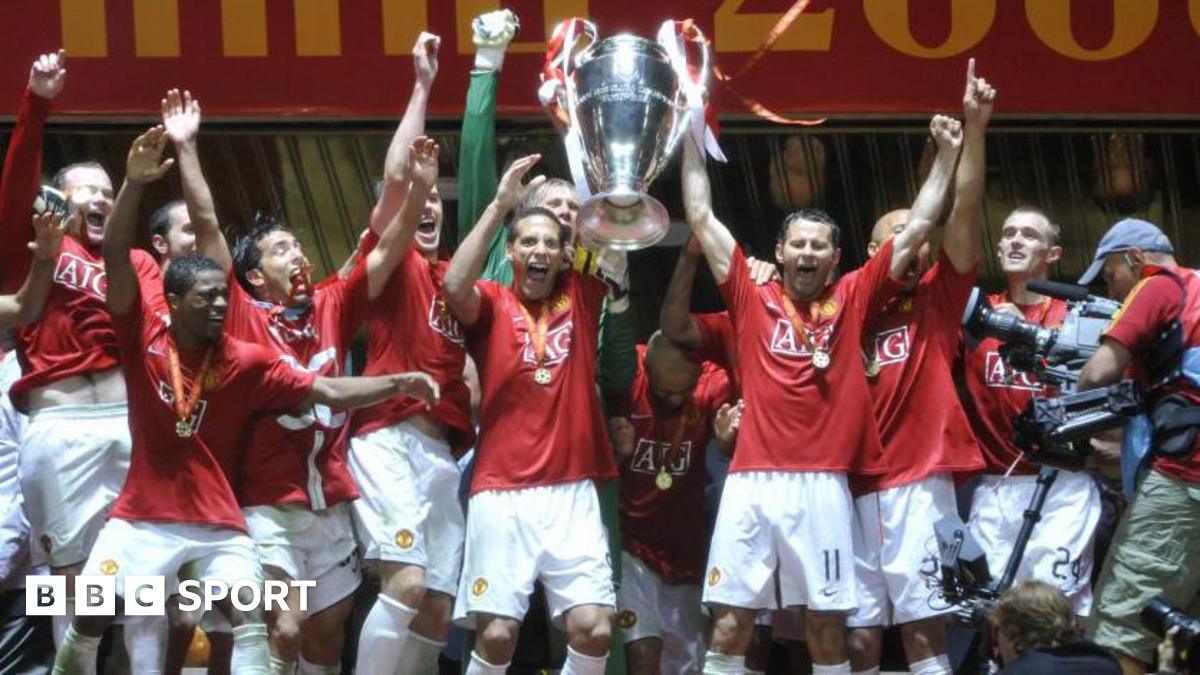

Getty Images

Getty Images

The former PM also suggested he regretted not doing separate media briefings just for children

"If you look at the sequence from February onwards, it's clear that Sage (Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies) is talking about the possibility, the Cabinet is discussing it in March. Certainly I remember the subject coming up repeatedly," he said.

It is right to say Sage had referenced the prospect of "mass school closures" in February 2020.

But the top civil servant at the Department for Education (DfE) at the time, Jonathan Slater, wrote in his evidence submitted to the inquiry that "DfE's contingency plans were premised on the assumption that schools (and other education settings) would remain open".

And Williamson told the inquiry last week that his ability to plan for closures was impeded by Downing Street.

It all points to the chaos of the decision-making processes at the heart of government at the time - something explicitly referenced in earlier evidence by the former children's commissioner Anne Longfield.

It wasn't clear who had responsibility for planning for children at the time, she said.

What is now clear is that there was no love lost between Johnson and Williamson, the people with the highest responsibility for children's welfare at the time of the pandemic.

Last week, we saw the expletive-laden rant Williamson texted to his former boss in which he lamented the "abuse" he had received for the government's decision to shut schools the day after reopening them in January 2021.

And on Tuesday, Johnson was confronted with his own leaked messages to his advisers, in which he suggested he wanted to fire those in the DfE after the exam results fiasco of August 2020.

He now says the DfE did a "heroic" job of trying to cope with the pandemic.

This was described as an "insult" by the Liberal Democrats "to the true heroes of the Covid pandemic: the teachers and doctors, nurses and key workers who put their lives on the line to keep crucial public services going".

Johnson now concedes that the lockdowns and social-distancing rules "probably went too far" - and there could have been a way to make children exempt.

These are all points that Baroness Heather Hallett, chairman of the inquiry, will be paying particular attention to when it comes to her final report, and the question of what could be done differently if it were ever to happen again.

In the inquiry room itself, no technology is allowed, no mobile phones or laptops, and so many of the journalists were in the press room upstairs watching the live feed.

Tuesday was busier than it has been over the last few weeks, and downstairs the public gallery was full. There was a reminder before proceedings began that hecklers were not allowed - a nod to the previous time Boris Johnson appeared, when protesters had to be escorted out of the building.

Campaigners from various groups, including Long Covid Kids and Clinically Vulnerable Families have been a noticeable presence outside the front door - trying to get their voices heard with placards and banners.

Boris Johnson is used to speaking to large crowds and at formal events like this, but at the end of the inquiry, when Baroness Hallett turned to thank him for his evidence, he was already trying to get out of his seat - clearly keen to finish up for the day.

He will likely be pleased not to be coming back.

3 months ago

71

3 months ago

71