John Sudworth

North America correspondent

Reporting fromBoston

MacPherson family

MacPherson family

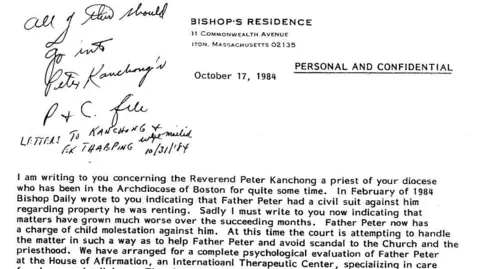

Alexa MacPherson (left) was sexually abused from the age of three by Priest Peter Kanchong (right)

As 135 cardinals meet in Rome to decide the next pope, questions about the legacy of the last one will loom large over their discussions.

For the Catholic Church, no aspect of Pope Francis' record is more sensitive or contentious than his handling of the sexual abuse of children by members of the clergy.

While he's widely acknowledged to have gone further than his predecessors in acknowledging victims and reforming the Church's own internal procedures, many survivors do not think he went far enough.

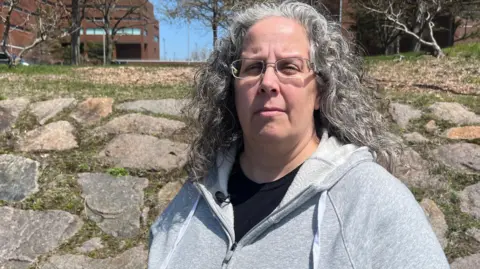

Alexa MacPherson's abuse by a Catholic priest began around the age of three and continued for six years.

"When I was nine-and-a-half, my father caught him trying to rape me on the living room couch," she told me when we met on the Boston waterfront.

"For me, it was pretty much an everyday occurrence."

On discovering the abuse, her father called the police.

A court hearing for a criminal complaint against the priest, Peter Kanchong, accused of assault and battery of a minor, was set for 24 August 1984.

But unbeknownst to the family, something extraordinary was taking place behind the scenes.

The Church – an institution that wielded enormous power in a deeply Catholic city – believed that the court was on its side.

"The court is attempting to handle the matter in such a way as to help Father Peter and to avoid scandal to the Church," the then-Archbishop of Boston, Bernard Law, wrote in a letter that would remain hidden for years.

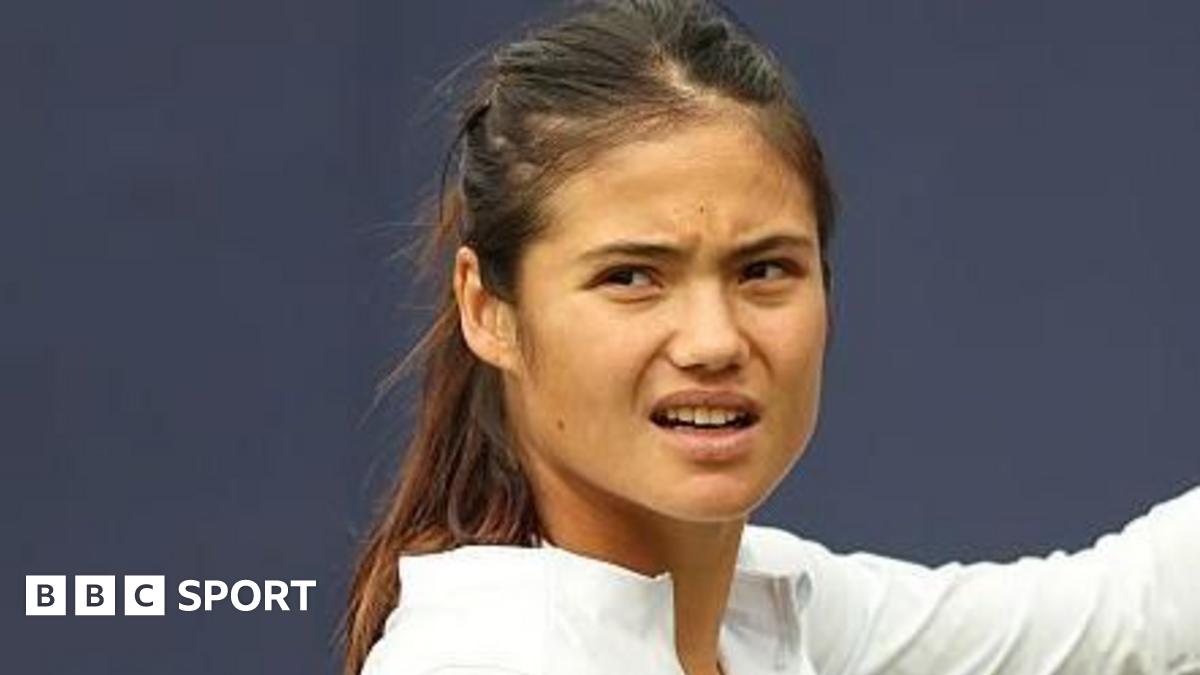

Alexa MacPherson believes there is so much more the Catholic Church can do about child abuse

Reflecting on the events of more than four decades ago, Ms MacPherson recognises that her abuse took place long before Francis became pope.

But over that same period, through a series of global scandals which are still unfolding, the issue of the systemic sexual exploitation of children has become the modern Church's biggest challenge.

It is a challenge she believes Pope Francis failed to rise to, as she made clear when I asked her how she had reacted to the news of his death.

"I actually don't feel like I had much of a reaction," she replied.

"And I don't want to take away from the good that he did do, but there's just so much more that the Church and the Vatican and the people in charge can do."

Uncovering the abuse

The 1984 letter from Archbishop Bernard Law was addressed to a bishop in Thailand.

Mentioning the accusation of "child molestation" it was written two months after the Boston court hearing, which had indeed concluded without scandal for the Church.

Peter Kanchong - who was originally from Thailand - had been spared from formal criminal charges and given a year's probation on the condition that he stayed away from the MacPherson family and underwent a course of psychological therapy.

The Archbishop's letter, however, noted that even the Church's own psychological evaluation had determined that the accused priest was "not motivated and unresponsive to therapy" and should therefore be "forced to face the consequences of his actions" under both civil and Church law.

But instead of acting on that advice, he implored the Thai bishop to immediately recall Peter Kanchong to his diocese in Thailand, mentioning for a second time the risk of "grave scandal" if he were to remain in the US.

Although press reports from the time suggest the Church authorities in Thailand did agree to take him back, Peter Kanchong ignored the recall, finding work in the Boston area at a facility for adults with learning disabilities.

In 2002, more than 18 years after Ms MacPherson's father first called the police, the archbishop's letter was made public.

In a landmark ruling, it was one of thousands of pages of documents that a Boston court ordered the Catholic Church to release.

Catholic Church

Catholic Church

A local newspaper, The Boston Globe, had, for the first time, begun to seriously challenge the institution's power in the city, by placing the stories of victims on its front pages.

Soon, hundreds had come forward and their lawyers were fighting in court to prise open decades of internal records relating to the sexual abuse of children.

The Church had tried to argue that the First Amendment protection for freedom of religion entitled it to keep those files secret.

The order to unseal them led to a watershed moment.

Contacted at the time, Peter Kanchong denied the allegations.

"Do you have evidence? Do you have witnesses?" he told the Boston Globe, who found him still living in the area.

Ms MacPherson, however, was one of more than 500 victims who won an $85m civil case for the abuse they'd suffered at the hands of dozens of priests.

The internal files showed that, time and again, Archbishop Law had dealt with his knowledge of abuse in the same way he'd attempted to deal with Peter Kanchong - by simply moving priests on to new parishes.

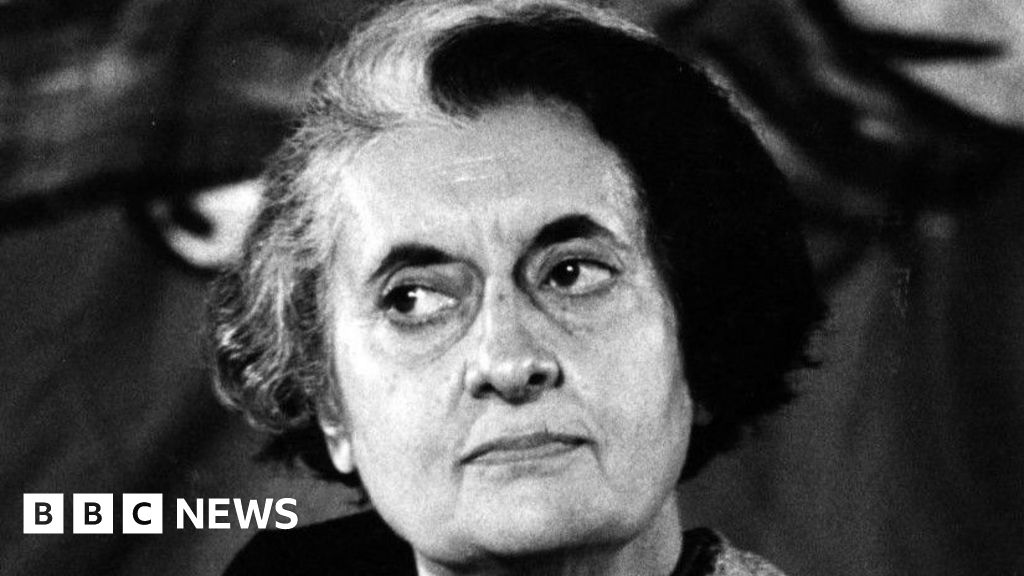

After the settlement, and by then a Cardinal, Bernard Law resigned from his position in Boston and moved to Rome.

For the survivors, the sense of Church impunity was further compounded when he was given the honour of a seven-year post as Archpriest of the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore, the same building where Pope Francis has now been buried.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Bernard Law died in Rome in 2017

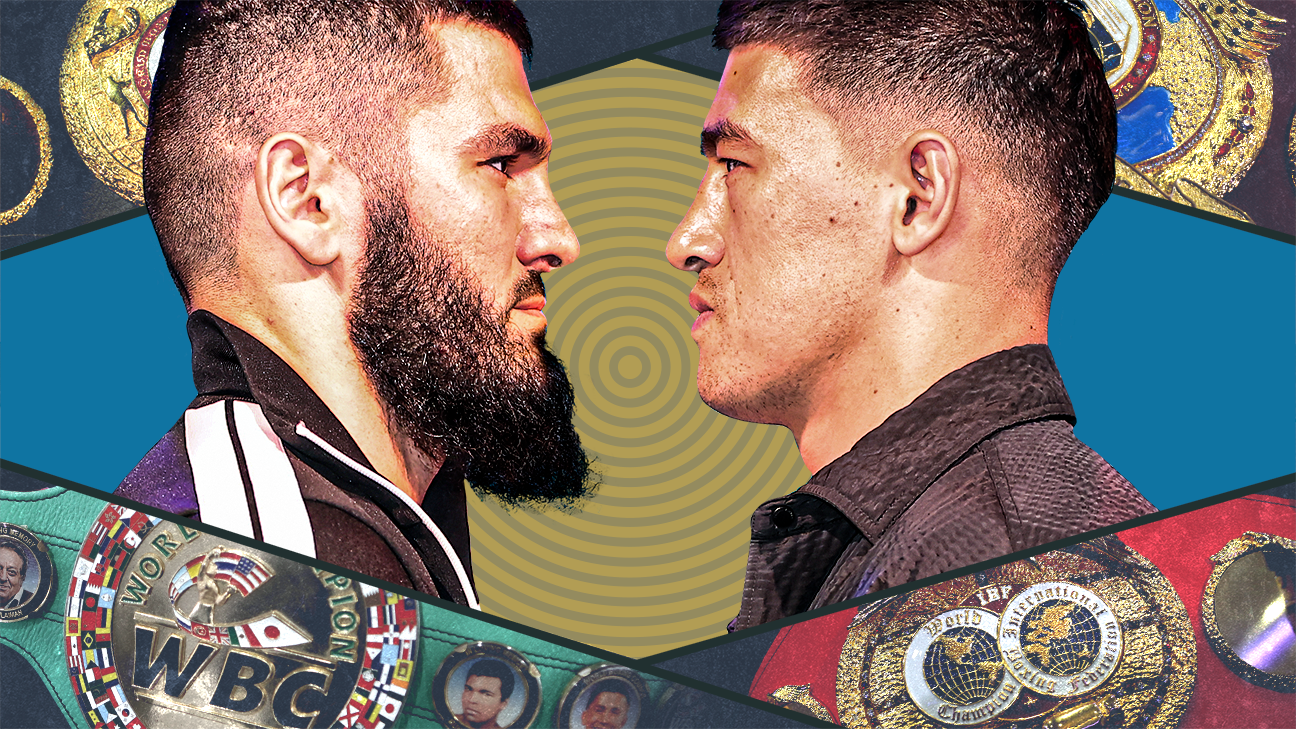

Many Church insiders credit Francis with going further than his predecessors to address the issue of abuse.

In 2019, he summoned more than a hundred bishops to Rome for a conference on the crisis.

In the abuse of children, he told them, "We see the hand of evil."

The conference led to a revision of the Church law on "pontifical secrecy" allowing co-operation with the civil courts when required in cases of abuse.

The change, however, doesn't compel the disclosure of all information relating to child abuse, only its disclosure in specific cases when formally requested by a legitimate authority.

Similarly, a new law requiring that allegations be referred up the internal Church hierarchy stops short of mandating referral to the police.

Ms MacPherson's lawyer, Mitchell Garabedian, a man portrayed in the Hollywood blockbuster Spotlight about the Boston abuse scandal, told me there are plenty of ways the Church continues to exercise secrecy.

"We have to litigate in court to get documents, nothing really has changed," he said.

His 2002 legal victory may have been a defining moment, followed by an avalanche of such cases in dozens of countries, but he has no doubt that knowledge of wrongdoing remains hidden in churches around the world.

"While he did some things, it's not enough," Ms MacPherson told me when I asked for her assessment of Pope Francis' record on this issue.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Critics believe Pope Francis didn't do enough to tackle the issue of child abuse

She wants the Church to reveal everything it knows.

"One of the biggest things is turning over predatory priests and the people who covered it up and holding them accountable in a regular court of law and not shielding them and hiding them any longer."

Watching the endless news of the Pope's funeral and the preparations for the appointment of his successor has been painful for her.

"It's the abuse being celebrated, in a way," she told me, "Because the cover-ups are still there, they're shielded behind the Vatican walls and their canon laws."

It is news coverage she's found hard to escape because of her mother's continuing faith in the Catholic Church.

"It's all I've heard on the news, and she is obsessed with watching this, and so I just get slammed and inundated with it."

Now 85-years-old, Peter Kanchong meanwhile has never been convicted of an offence.

Nor has he been stripped of his priesthood, although he has been prevented from holding any formal position in the Boston Diocese.

The Church's own published list of accused clergy marks his case as "not yet resolved" with no final determination of guilt or innocence, noting simply that he is "AWOL" - absent without leave.

"I've been trying for years to have him defrocked and that is because he can only be defrocked either where he was ordained, which was in Thailand, or by the Vatican," Ms MacPherson said.

She points out that the Church has gone to the trouble of changing the name of the parish where she was abused - in order, she believes, to try to start afresh after what took place there.

The BBC asked the Boston Diocese for its views on Pope Francis' legacy as well as for a response to claims that the Catholic Church maintains a culture of secrecy over its own internal records.

We received no reply to those questions.

We also asked whether the current archbishop could do anything to help victims seeking to remove a priest from the priesthood.

We were referred to the Vatican.

As the Catholic Church now sets about the business of electing a new pope, Ms MacPherson holds little hope for more comprehensive reform.

"You say you want to move forward. You say you want to bring people back into the fold," she said.

"But you cannot possibly do any of that until you truly acknowledge those sins, and you hold those people accountable."

1 month ago

46

1 month ago

46